We saw a spectacular explosion in speculative activities in the aftermath of the COVID lockdowns, the likes of which we have never seen in our lifetimes. Old-timers in the markets tell me there were a few crazy phases in the 90s, but we’re talking analog craziness, not digital craziness—that’s an apples-to-Paragon-slippers comparison.

In the years since COVID, there’s been a great deal of concern, debate, and shrill noise about speculative activities and their societal impact in India. These debates have reached fever pitch in the last couple of years, so much so that politicians have gotten in on the action.

As someone who spent a decade in a brokerage company with a front-row seat to the evolution of Indian capital markets, I have some things to say. I’ve been meaning to write about this issue for a couple of years but have been too lazy to. However, the recent ban of gaming and betting apps by the government has rekindled the debate over the real damage caused by speculative activities and what the right approach is to regulating them. So I figured now is as good a time as any to share my opinions nobody asked for.

Instead of sharing a hot take on the betting apps ban, I want to approach this issue from my experience of working in a broking company and watching the transformation of Indian capital markets. The reason is that, much like the concern around the detrimental effects of gaming and betting apps, there was a similar concern over the popularity of derivatives (F&O) among retail investors in capital markets.

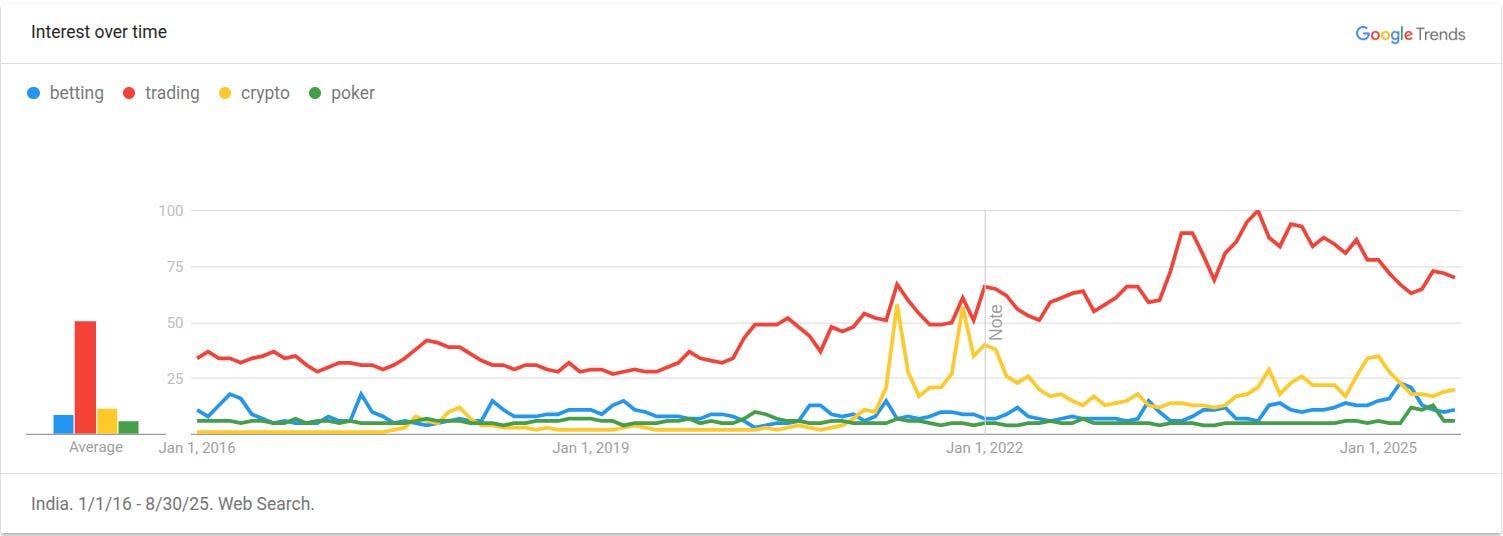

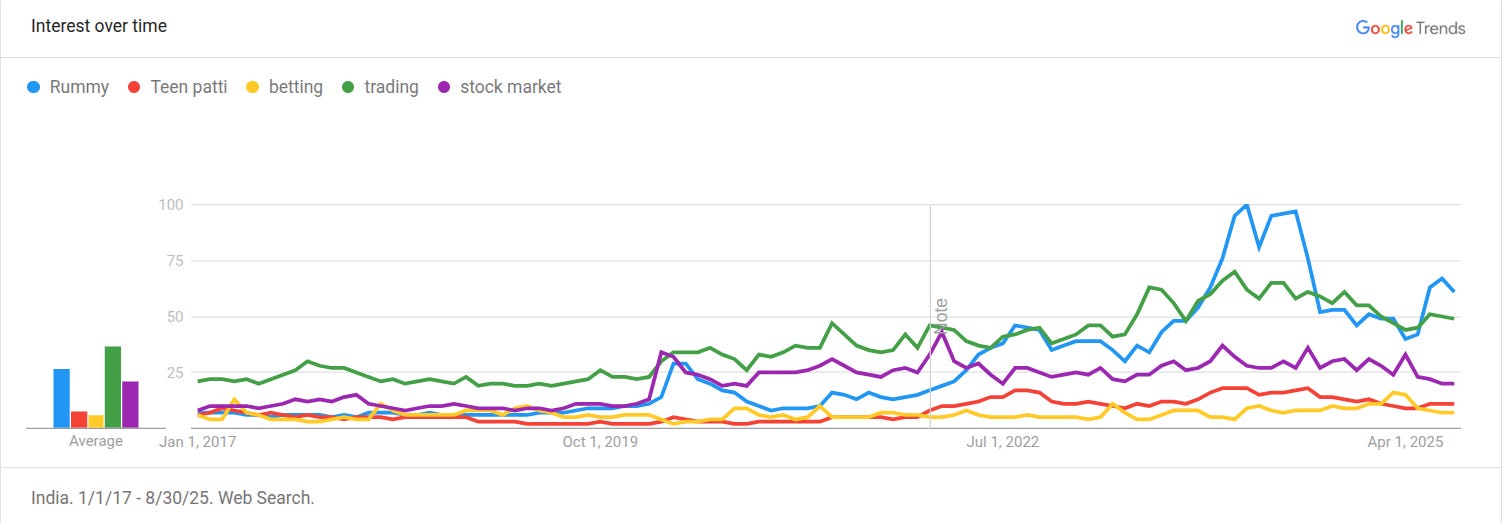

The concerns around betting apps and F&O came to the fore around the same time and follow a similar narrative arc because both became popular after COVID. You can trace the popularity of betting apps alongside the popularity of trading and investing apps.

The factors that enabled the popularity of both these speculative avenues are the same. In watching the Indian stock market transform, I’ve also followed the evolution of the very nature of speculation both in capital markets and outside.

The prelude

I joined Zerodha around 2017, right when all the factors that enabled the popularity of trading, investing, and betting apps were going live. The first and perhaps most important trigger was Aadhaar and eSign, which made investing fully online. Then UPI made payments instant and free, and finally Reliance Jio brought millions of Indians online with its cheap data plans.

Along with all of this, the generous non-80C donations by VCs to fintech companies across investing, payments, gaming, and lending played a massive but underappreciated role in popularizing trading and investing. All of these factors were making the markets popular, but at the same time, they were helping expand the surface area of speculation. Coincidentally, many gaming and betting apps were raising funding around the time VCs had a hard-on for stockbroking companies.

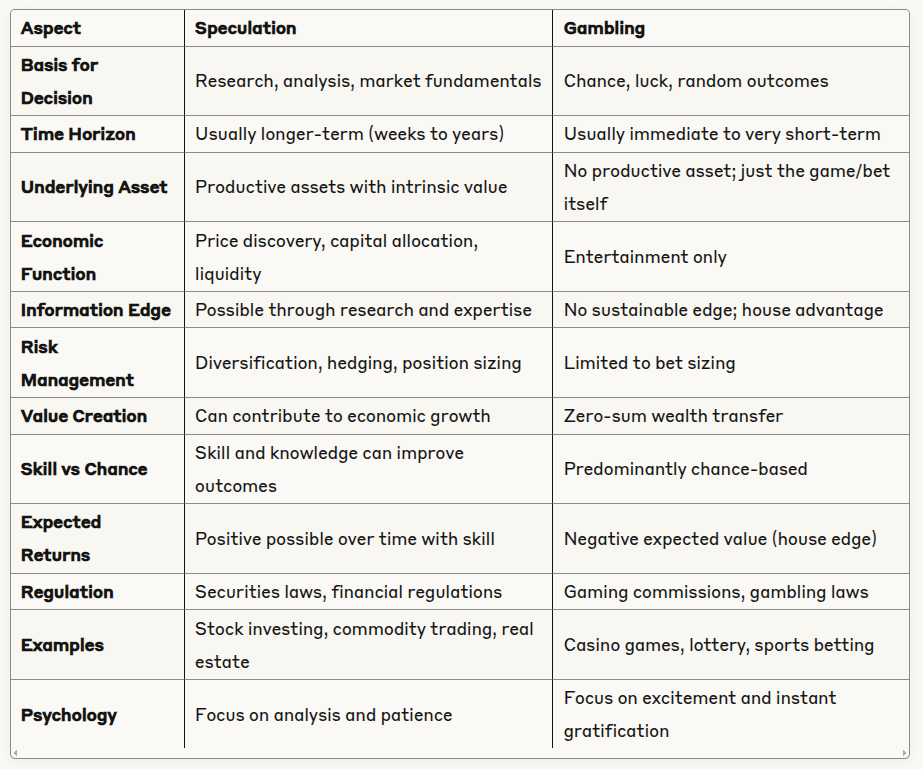

By 2020, all the pieces needed to enable speculation and gambling to go mainstream were in place. As an aside, I’m choosing to distinguish between speculation and gambling. The semantic similarities aside, in speculative activities like trading and investing, you can manage your risk to an extent and have a sense of the potential payoffs. In many cases, you can even define your risk-reward payoffs, and to a large extent, that’s not possible with gambling.

Ultimately though, there’s a large degree of chance and luck involved in anything where the future has a role to play, as is the case with both speculation and gambling. Everything from your career, marriage, or taking a flight has both characteristics.

I asked Claude for the difference between speculation and gambling:

The COVID catalyst

The trigger that unleashed the ravenous desire to speculate among millions of Indians was ironically made in China, probably in a lab or in the stomach of that fellow who ate that undercooked bat or pangolin or the unholy lovechild of a muskrat and pangolin—COVID-19.

When COVID hit and lockdowns began, Matt Levine’s “boredom market hypothesis” took over. Normally people had numerous options to have fun because they weren’t locked in their homes. They could go out and do a hundred things to enjoy some cheap thrills. After COVID, going out was no longer an option, and the only outlet for people to get some cheap thrills was through their phones.

As the world was locking down, all the pieces needed for people to find a release for their boredom were in place. Cheap internet thanks to Jio. Instant account opening. Seamless payments. Everything was digital. Because of these same innovations, borrowing money had become instant too, adding fuel to people’s speculative urges. The final recipe in this heady mix was the extreme lack of friction in the apps. This was a potent mix that led to a spectacular explosion in speculative activity that India had probably never seen at this scale.

This speculative activity was spread across the stock market derivatives, gaming apps, betting apps, crypto trading, fantasy sports, and God knows what else.

We’ve had speculative episodes before—the dot-com bubble, the Harshad Mehta bull run, pre-2008, and so on. But those were all pre-internet and always localized. The post-COVID period was the first time speculation spread across everything and everywhere.

Even today, I don’t think we’ve really understood how dramatic this post-COVID phase has been or how speculative activity spread across capital markets and other areas.

The water always finds its way

This explosion in speculation and gambling freaked people out. Politicians, regulators, and commentators were worried about people gambling away their life savings in F&O, gaming and betting apps, crypto, and so on. There was a steady increase in people committing suicide because they had borrowed to speculate and gamble. This added narrative fuel to the fire.

Not only were people in power and the commentariat worried, but they also wanted to save people. This led to a minor miracle, which created more Jesus-like figures since, well, Jesus’s apostles.

There were serious…ish efforts to curtail speculative activity in the stock market, crypto space, and gaming apps. Many regulations were passed, some good, some bad, but mostly ineffective. Trying to curtail speculative and gambling instincts without careful thought about regulatory design is like playing a game of whack-a-mole while being blindfolded and high on local ganja.

In watching all these interventions to reduce speculation and gambling, I realized something: speculation is like water, it always flows downhill.

Humans have gambled as long as they’ve been on this planet and will continue to do so. Who knows, once the robots replace us, maybe they’ll also gamble?

The reality is that people will gamble in legal ways when possible and illegal ways when not. The urge to speculate, to chase cheap thrills, is biologically ingrained in us. Until scientists figure out an affordable way to rewire or surgically remove the prefrontal cortex of 8 billion people, there will always be a gambling instinct.

The gambling instinct is fundamental human nature. You can find it everywhere. The earliest evidence of gambling dates back to ancient Mesopotamia around 3000 BCE. Knucklebones, a game believed to be the precursor of dice, was played using ankle bones of sheep and other animals. Lottery-type games were played in China as far back as 2300 BCE. The dice game between the Pandavas and Kauravas is central to the Indian epic Mahabharata. Hell, pick any religious text, and the gods are regularly rolling dice, just with much higher stakes, like the fate of the entire bloody universe.

I recently learned that in the late 1800s, Indians gambled on rain.

Yes, bloody rain.

That watery thing that falls from the sky when you don’t want it and ruins a laundry day.

On 20 March, 1897, the Bengal Legislative Council introduced a bill calling for the specific banning of a practice called “rain gambling”.

Rain gambling, also known as Barsat ka Satta, was a form of speculation where people would place bets over future rainfall, i.e., the quantity and duration of rain during a window of time, when the monsoon would arrive, and how long it would last. This form of betting was especially popular with the Marwari community, who brought it with them from Rajasthan as they emigrated to various parts of India… including Bengal.

You’d think that betting on rainfall would be a random pastime activity, but it was anything but. In fact, it got so popular that the British colonial government got quite concerned, going so far as to even amend laws to ban the practice in Bombay (now Mumbai).

Some of our most foundational discoveries are the result of gambles. Every startup is basically a bet on an unproven idea. Drug companies spend billions gambling on compounds that mostly fail. Venture capital is literally betting on entrepreneurs with nothing but a pitch deck. Columbus gambled on a western route to Asia. Even insurance is just betting against disasters.

It’s gambles all the way down, brah!

Of course, there are good gambles and bad gambles. Bad gambles sometimes teach people useful things about risk and probability. Hell, I’d argue that gambling in stock markets has taught more people about finance than all the financial literacy programs combined.

True story.

But here’s the thing: speculation is like water, it always flows downhill. Regulators can build dams and barriers, but the water just finds new channels.

Exhibit A: where the action goes

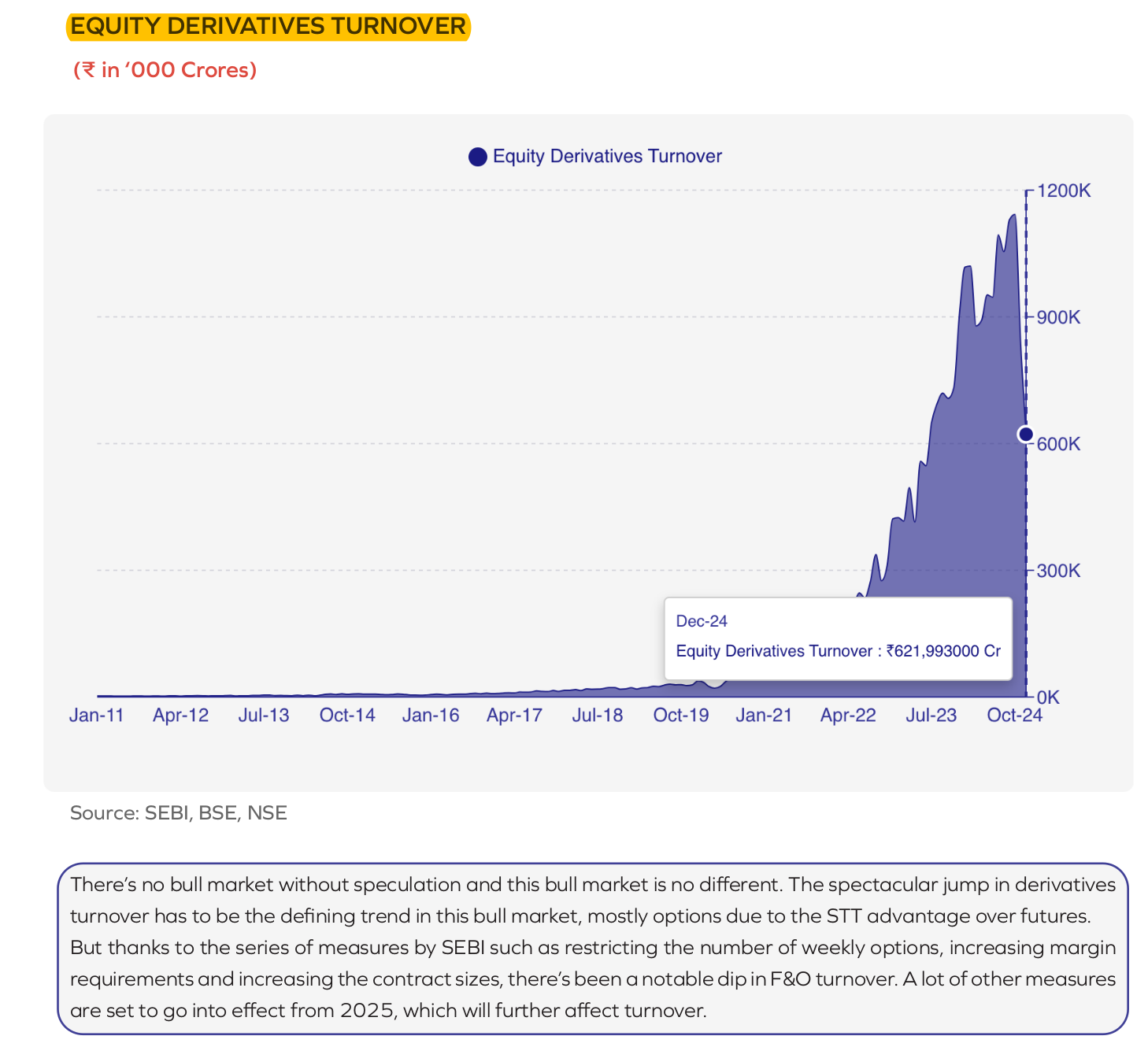

Take derivatives. In the post-COVID period, there was a spectacular increase in derivatives trading. There was a massive influx of uninformed retail investors, and 90% of them lost money in F&O.

Given the speculative fervor and losses among retail investors, SEBI became concerned and implemented a series of measures in the last couple of years to make trading F&O unattractive. In a sense they worked, and F&O volumes are down significantly.

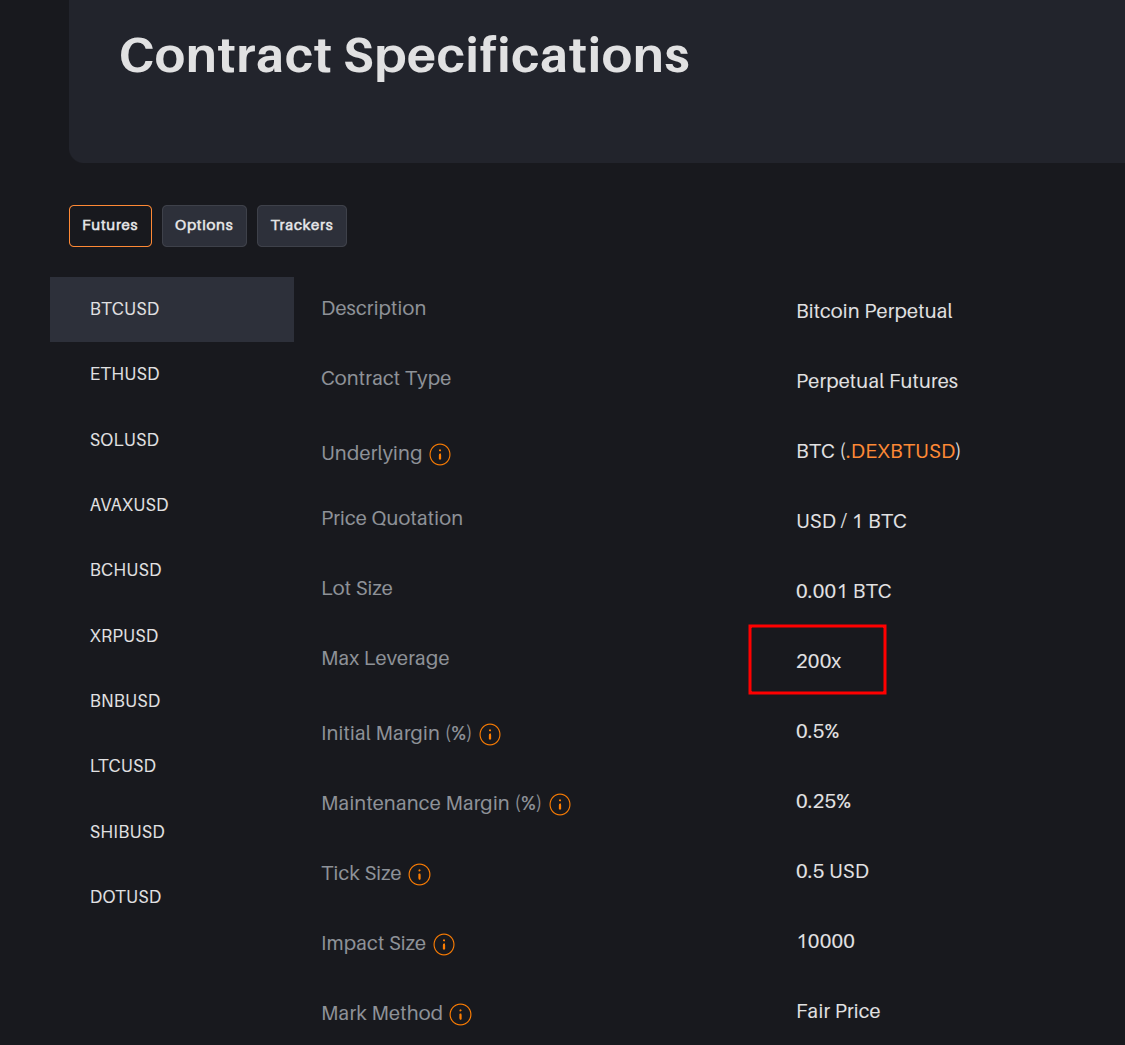

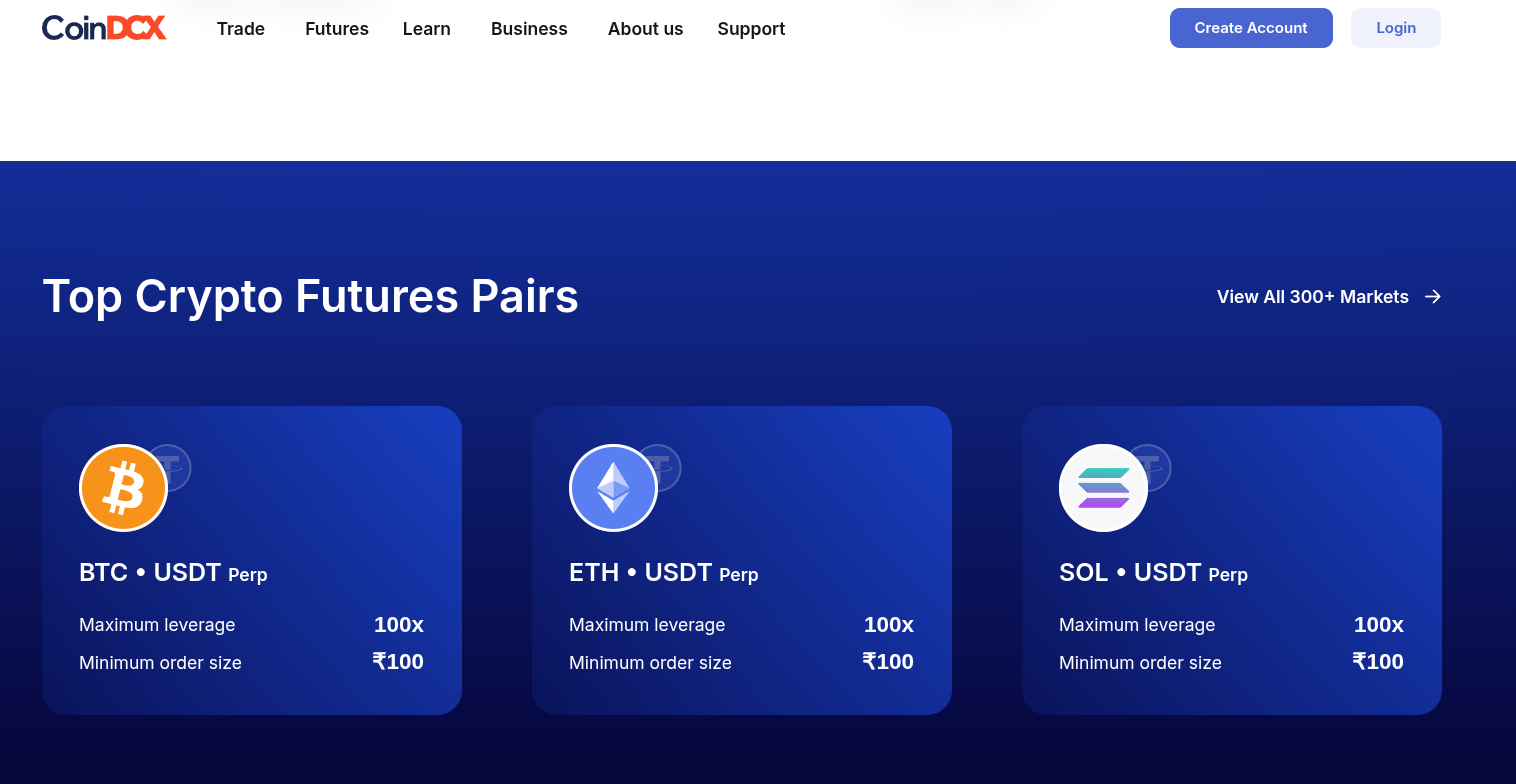

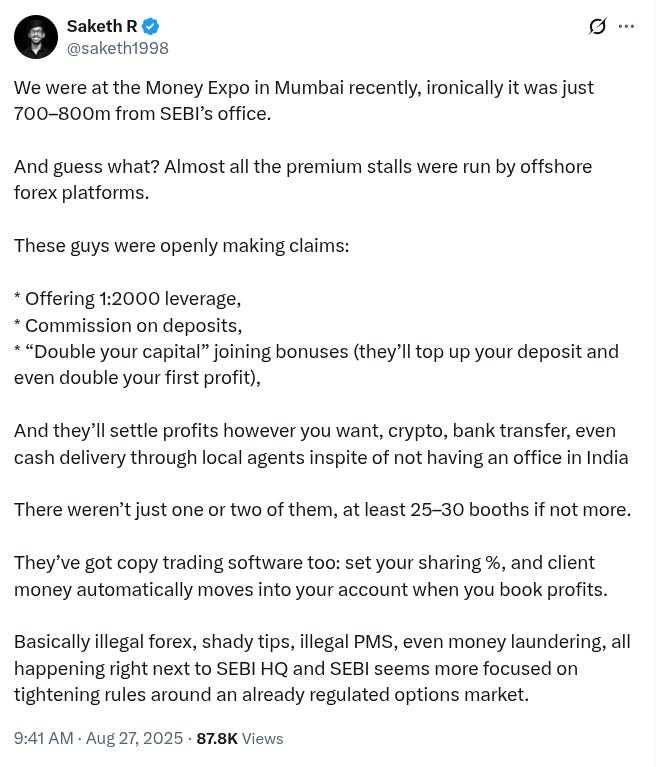

However, the urge to speculate is like water, and it always finds an outlet. After it became unattractive for many traders to trade F&O, crypto derivatives have become popular in the last year or so. Now, crypto derivatives exist in a legal vacuum, and without any oversight, they’re openly advertising leverages of 100-200X.

Where there are gamblers, there are dealers.

It’s not just crypto derivatives, but a whole host of shady forex platforms are trying to attract the traders who want lower margins and higher leverage. The regulatory vacuum around crypto derivatives has created exactly what regulators were trying to prevent, just in a different channel.

The same story

In 2023, the government tried to restrict betting activity and imposed a 28% GST on the full value of the bets to discourage activity.

It didn’t.

What ended up happening is the govt ended up collecting thousands of crores in taxes.

Crypto was the same. Heavy taxes didn’t stop anything. If anything, it seems to be picking up again after that initial dip. Now imagine what will happen with gaming and betting now that these activities are banned.

And, right on cue, I just came across this ET article that shows offshore betting apps are trying to fill the vacuum:

The ban on online real money gaming (RMG) may have left homegrown platforms staring at the extinction of their business model but offshore betting websites are rushing in to fill the gap, said industry executives. Platforms such as Parimatch, 1XBet, RajaBets, 4RABet and Odds92 are busy pulling in the punters, boasting deposit bonuses ranging from 200% to 700% on amounts between Rs 30,000 and Rs 1 lakh, along with add-ons such as 500 free spins, ET has discovered. That means for a deposit of Rs 100, a user could get credit ranging from Rs 200 to Rs 700, going by the claims.

A small irony

What’s funny in all of this is that the government has unwittingly and unknowingly enabled this speculative mania. I’d argue that without initiatives like Aadhaar, DigiLocker, and UPI, these gaming and betting apps would’ve been far less popular. UPI was meant to make payments accessible, and it also made it possible to bet ₹10-20. The same lending innovations that made borrowing instant also made it easier for people to bet with borrowed money. Without that infrastructure, small bets and leveraged speculation would’ve been way less viable.

Indians wouldn’t be spending Rs 10,000 crores a month on gaming and betting without all of these innovations. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying we shouldn’t have created UPI. The social welfare from instant payments far outweighs the harms by an order of magnitude. What I’m saying is that the entire saga around trying to regulate speculation and gambling proves that regulating these activities is way more complex, and knee-jerk reactions rarely work.

The law bans users from playing any kind of game for money, whether a game of skill or luck. And that includes games such as rummy, poker, and fantasy cricket that have survived for nearly two decades. On average, Indians spend over Rs 10,000 crore a month and at least 20–25 minutes a day on these games.

Aggregators such as Cashfree and Razorpay, in fact, built a thriving business catering to real-money gaming companies, growing not just their volume of transactions but also margins. In July, online games accounted for about 350 million UPI transactions. In 2024, people spent Rs 50,000–60,000 crore on real-money games, and that was expected to double this year, said a senior payments executive. “No other sector grows as much,” they added. — The Ken

These numbers don’t fully capture the money that goes into shadier apps, would be my guess. So that number will probably be much higher.

You can’t have it both ways

Looking globally makes this clearer. The US has some of the biggest, deepest financial markets in the world. It’s also a gambling paradise. For the most part, you can’t have one without the other.

How do I put this nicely?

The degen gamblers are liquidity providers, and they provide a valuable social utility by losing money :p Their self-sacrifice deserves our respect.

Ok, I’m kidding.

It’s definitely possible to dampen speculation, and it’s possible to make degenerate gambling unviable and uneconomical, but that requires careful regulatory design, implementation, monitoring, and broad-based coordination. Isolated regulations and measures will always backfire.

What do I mean by that?

-

In Australia, online casino-style games are illegal, and since 2019, the Australian regulator has blocked 1,296 sites and forced ~220 services to exit, yet mirrors and rebrands keep popping up. Influencers are even openly promoting them.

-

China made gambling illegal on the mainland, but this has led to a spectacular explosion of offshore gambling operations across the Philippines, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and other Asian countries catering to the Chinese. To make things worse, these operations are deeply involved in transnational crime, scam operations, and human trafficking.

-

Norway operates a state-run gambling monopoly, and only two state-owned entities can offer gambling products. Despite this, anywhere between 20-30% of the activity happens on unlicensed platforms.

-

The Netherlands has a comprehensive licensing and regulatory framework for gambling and claims that up to 95% of all gambling happens on licensed platforms, but there are question marks over this.

So, the ideal amount of speculative and gambling activity in a society is non-zero.

When it comes to my industry, the financial markets, it is a truism that you can’t just have the good financial activity while stopping all the excess. If everybody becomes a long-term investor, how will markets function?

The costs of gambling

I don’t need to cite research to show that allowing all speculative and gambling activities without any constraints and guardrails is a bad idea. I’m sure people with libertarian persuasions would like that, but as someone who bought a subscription to Jacobin recently, I’m not in that camp.

At an individual level, excessive gambling can lead to anxiety, depression, loss of productivity, debt burdens, and, in the extreme, suicide. At a familial level, gambling leads to loss of trust, domestic conflict, broken families, and lifelong scars on kids. At a societal level, communities can experience higher degrees of homelessness, stress on social services, lost productivity, fraud, theft, and additional burdens on legal and law enforcement systems. All this can ultimately manifest in widening inequality.

I don’t envy the regulators. To my mind, there seems to be an irreconcilable tension between letting markets flourish and controlling speculation. I wouldn’t hesitate to say that the goals are fundamentally incompatible. Of course, this raises questions about the objective function of both regulations and markets, but that’s a debate that goes to the heart of capitalism, and as tempted as I am to settle that once and for all, I’ll resist the urge.

“What are you saying, bro?” you ask.

It’s important to look at this entire saga from different frames.

One of the most important frames is that of incentives. What’s the reason the government is banning these gaming and betting apps? After all, it’s foregoing a decent chunk of GST revenue. Vivek Kaul had a nice take in a recent article:

The media is full of news reports about individuals who played these games, lost large sums of money, fell into debt, and in some cases, took their own lives. These are the identified lives.

In this scenario, people are talking about the negative impact of these games. It’s an everyday conversation happening all around. So, the government needs to be seen to be doing something about the issue, the identified lives, that is.

If I were the government, I’d probably do the same, but there are downsides. I’m reminded of the famous story of Hercules’ Labors. As penance for killing his family in a fit of madness, the great Greek hero Hercules had to complete 12 tasks. One of the tasks was to kill the Lernaean Hydra, a multi-headed serpent that lived in a swamp. The issue was that the hydra had regenerative abilities, and one of its heads was immortal. For every head that was cut off, two would sprout, and this proved a challenge for Hercules.

Initially, Hercules tried using his famous brute strength to kill the monster but was predictably unsuccessful. Luckily, his nephew Iolaus had accompanied him, and together, they came up with a new plan. As soon as Hercules cut off a head, Iolaus would use a burning torch to cauterize the stump of the neck, preventing a new head from growing back. As for the immortal head, Hercules cut it off and buried it under a massive boulder, trapping it forever.

This is a perfect metaphor to think about bans on gambling and speculative activities. Trying to ban them is akin to killing an immortal multi-headed hydra—cut off one head and two new gambling apps will sprout.

I did a cursory literature review in preparing to write this post. The bottom line is that banning gambling and speculative activities can reduce the visible activity, but a significant chunk of it always migrates elsewhere. Until regulatory actions are paired with and coordinated across ISP/DNS blocks, payment-rail controls, app-store restrictions, advertising restrictions, and cross-border policing, demand often leaks offshore or underground and, in many cases, into criminal ecosystems.

This probably explains why many European countries try to channel activities onto regulated platforms while trying to promote harm reduction rather than prohibition alone. Is this the right way?

That leads to the other critical aspect in such regulatory interventions.

We need to study what we do

It’s easy to pass regulations but tough to know if they are successful. Until governments and regulators study their interventions, or unless there’s a research ecosystem that studies them, everything is useless.

Unless the first- and second-order effects of policies are studied, what’s the difference between a smart policymaker and some drunk person who happens to be in charge?

Many regulatory interventions that try to curb speculative activities show activity dropping in one area, but they never track where that activity goes. Without actually studying what works, we’ll keep coming up with dumb solutions for complex problems.

A lot of times, it feels like regulators cut off their nose to spite their face. That’s just counterproductive.

Finding the impossible balance

Now, based on everything I’ve said so far, you might think that I’m advocating for letting gambling run wild.

No.

Like I said earlier, crazy speculative activity comes with huge social costs. It ruins people’s lives, destroys families, creates debt problems, and can even threaten financial stability. 2008 showed us what that looks like when institutions do it, and ultimately, what are institutions if not a collection of individuals?

But I’m also not saying give up on regulation because it’s hard. I’m saying that because speculation is like water flowing downhill, we need to think really carefully about how to channel it.

Some gambling in any society is probably inevitable. The trick is creating smart guardrails that make the worst excesses uneconomical while recognizing that speculation is like a virus that constantly mutates. This makes regulatory coordination across all nodes in the ecosystem imperative.

Without proper frameworks and the ability to actually enforce rules, any attempt to stop gambling will probably just lead to weak results and unintended consequences. Implementation is always easy; measurement and enforcement aren’t. Unless these capabilities are built, we’ll be replaying this drama at regular intervals.

In watching the Indian stock market transform, I’ve realized that innovation always comes before regulation. Where people want to speculate, someone will always provide a way—regulated or not. The question isn’t whether to allow speculation, but how to channel it smartly while understanding that, like water, it’s going to flow downhill no matter what we do. Complete prohibition is impossible because you can’t regulate human nature.

Understanding this painfully obvious truth is the first step to making policies that actually work, instead of half-baked measures.

“There are no solutions. There are only trade-offs.” ― Thomas Sowell

Featured image: The Dice Players” by Georges de La Tour