Premeditatio malorum or negative visualization is a Stoic practice of imagining potential misfortunes and setbacks. The purpose isn’t to make oneself miserable but to build resilience by mentally rehearsing adversity and preparing for life’s inevitable challenges. They should’ve called it ‘make yourself depressed deliberately’ but no one would want to be Stoic then I guess.

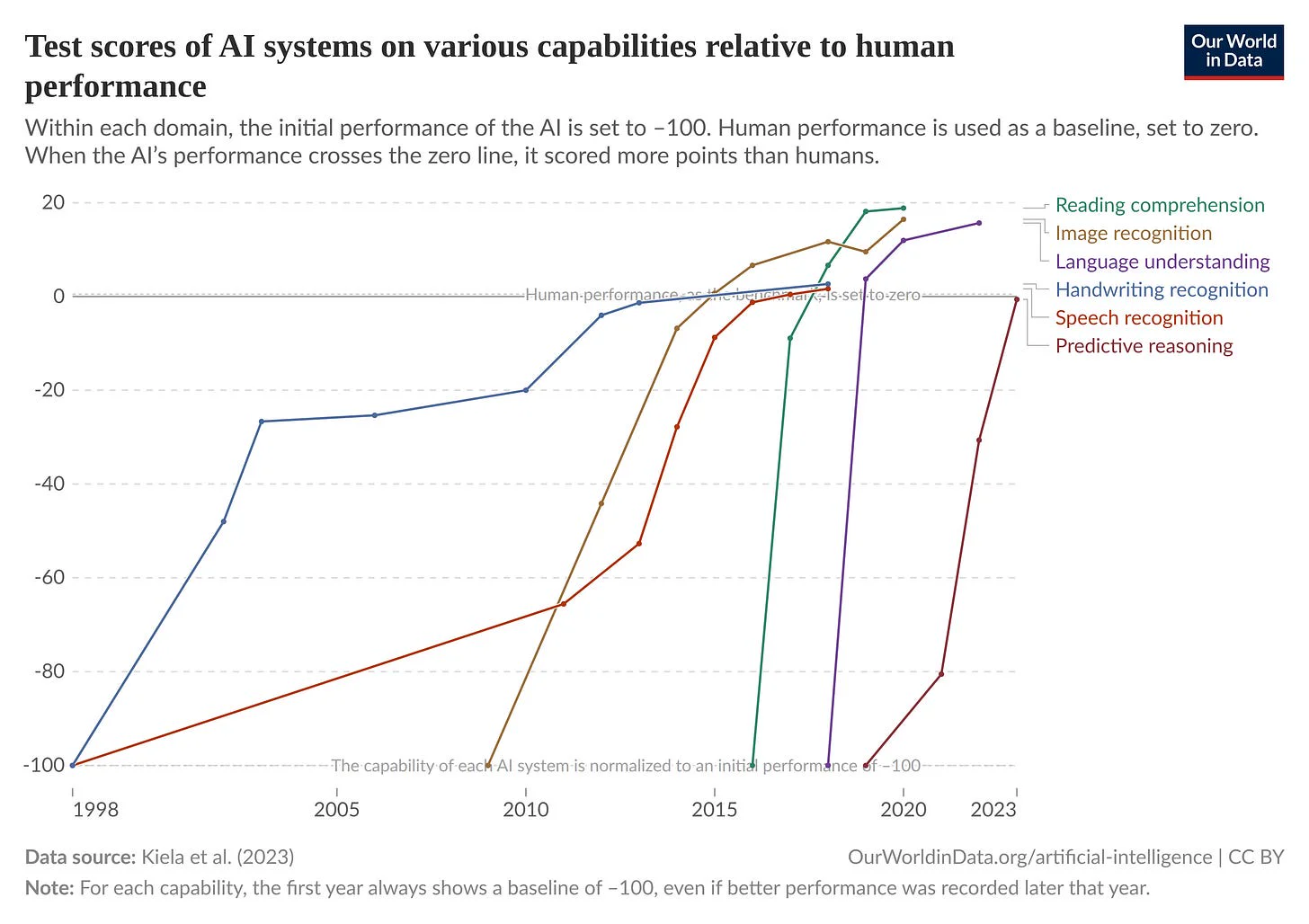

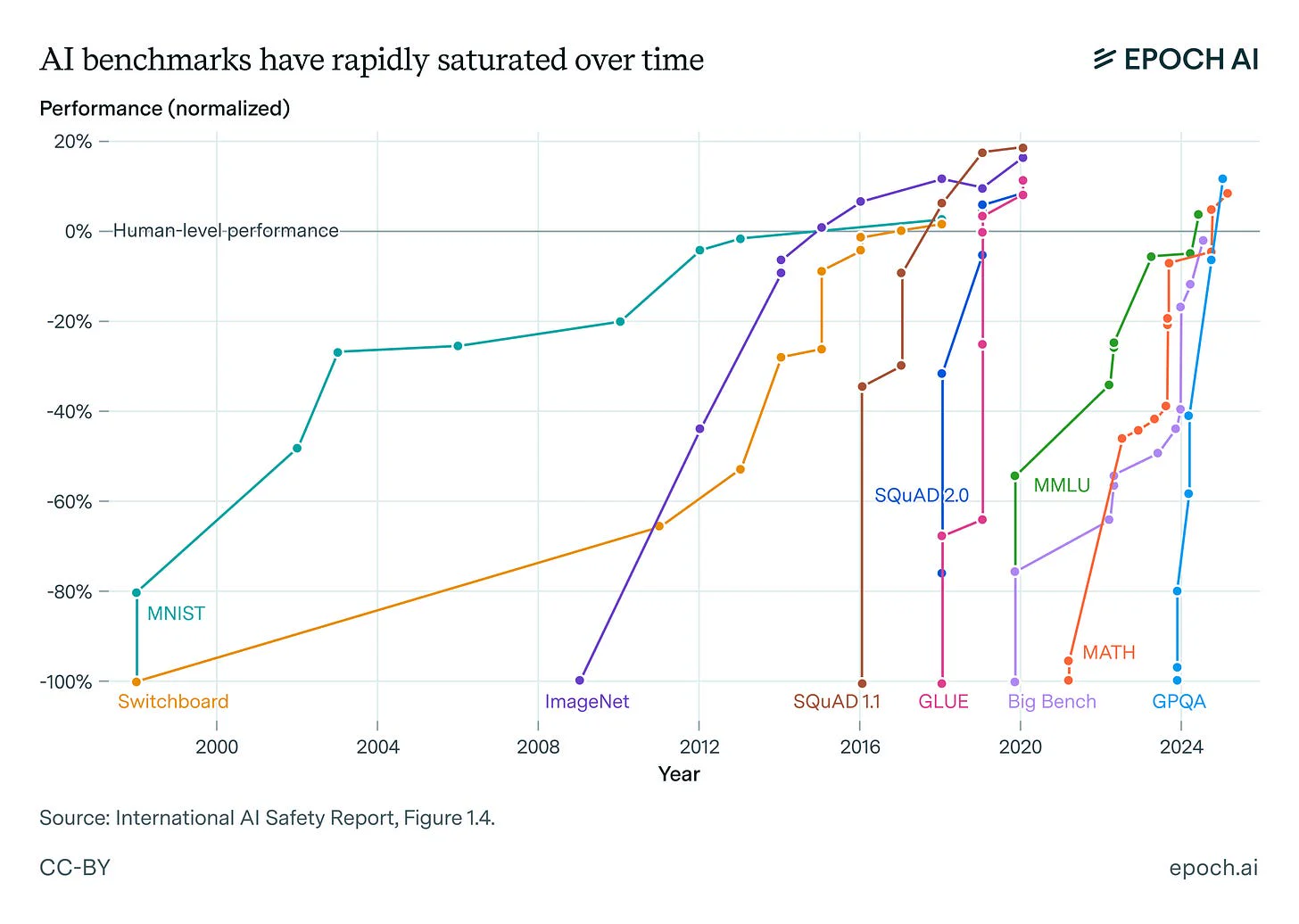

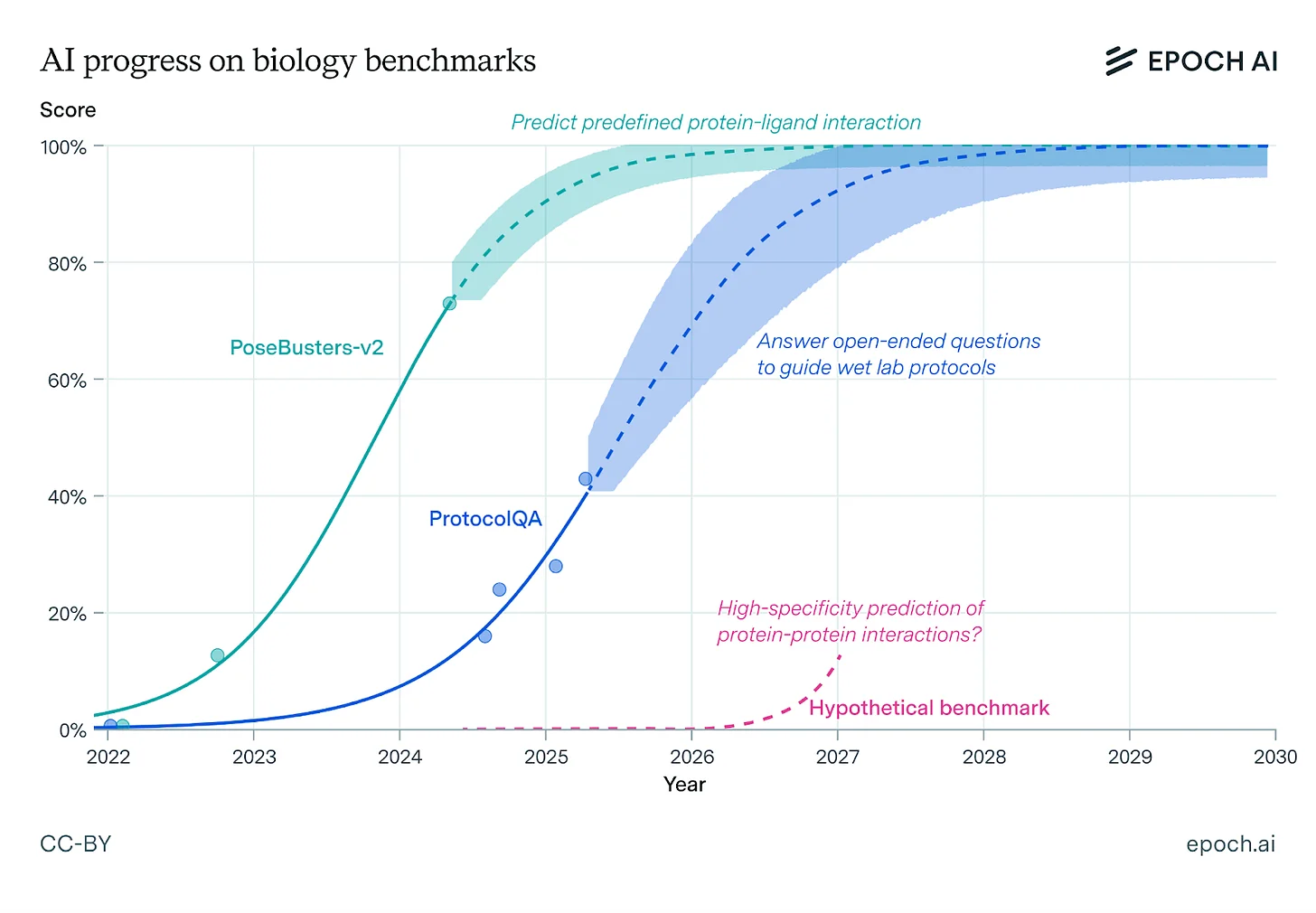

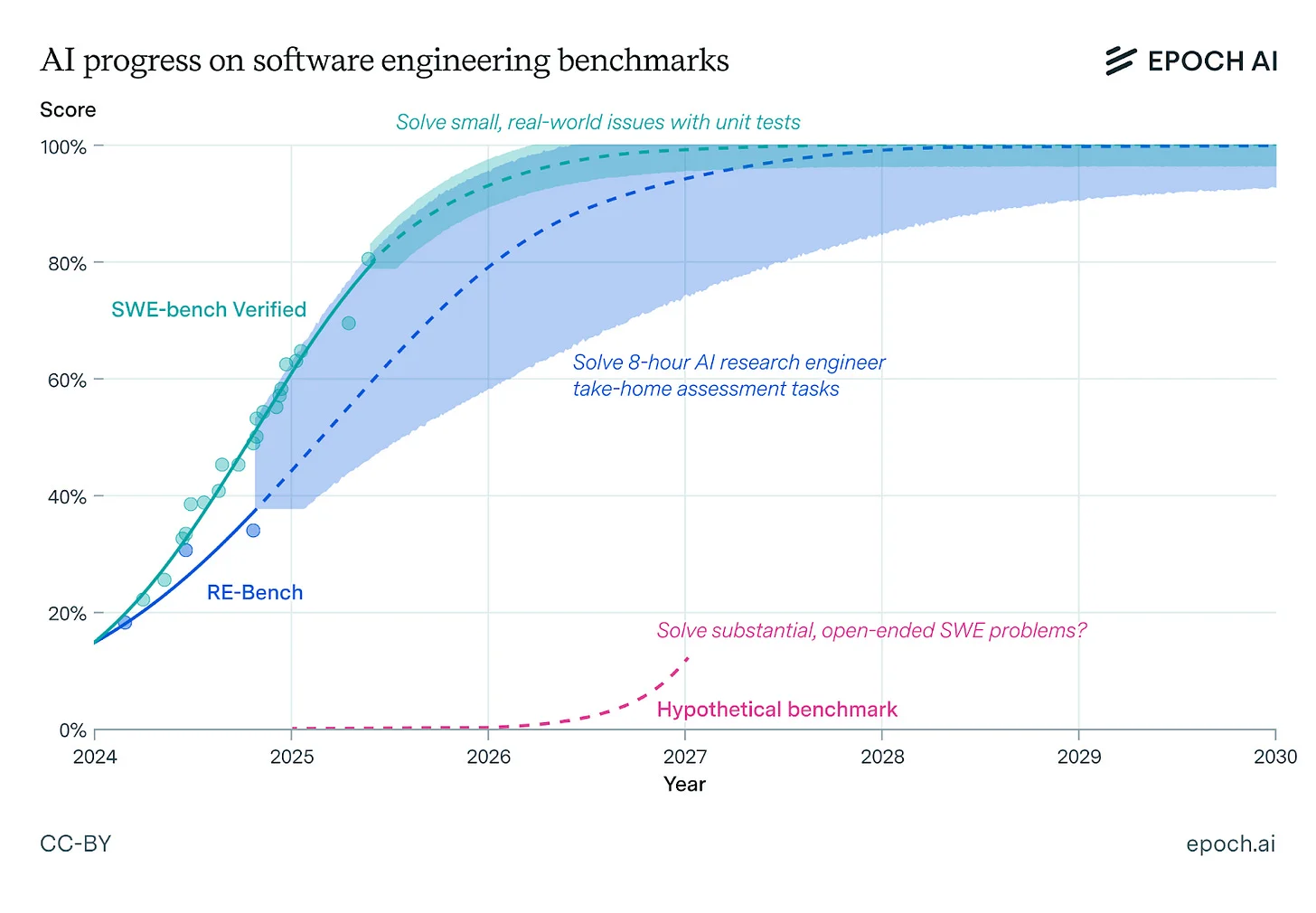

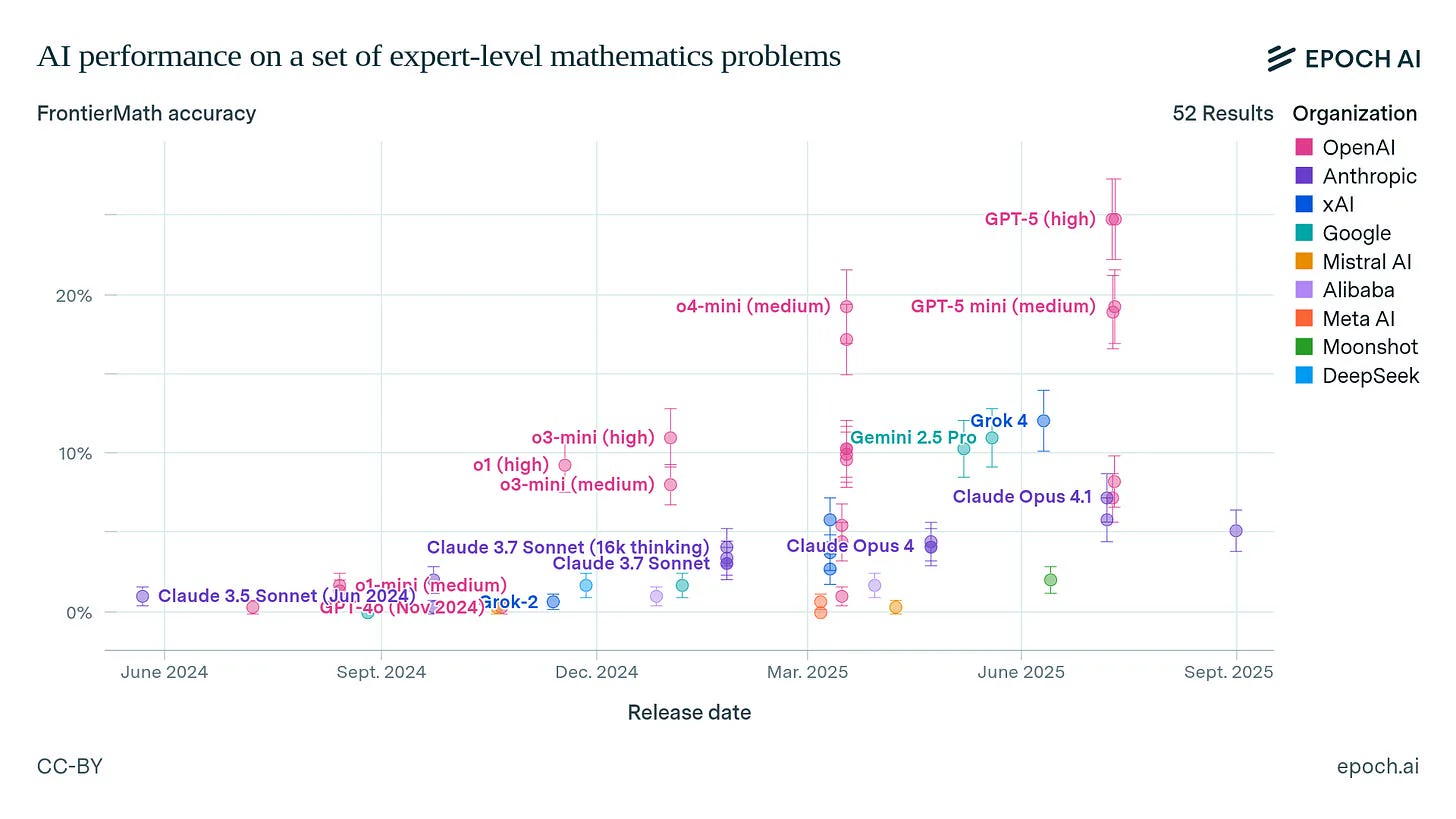

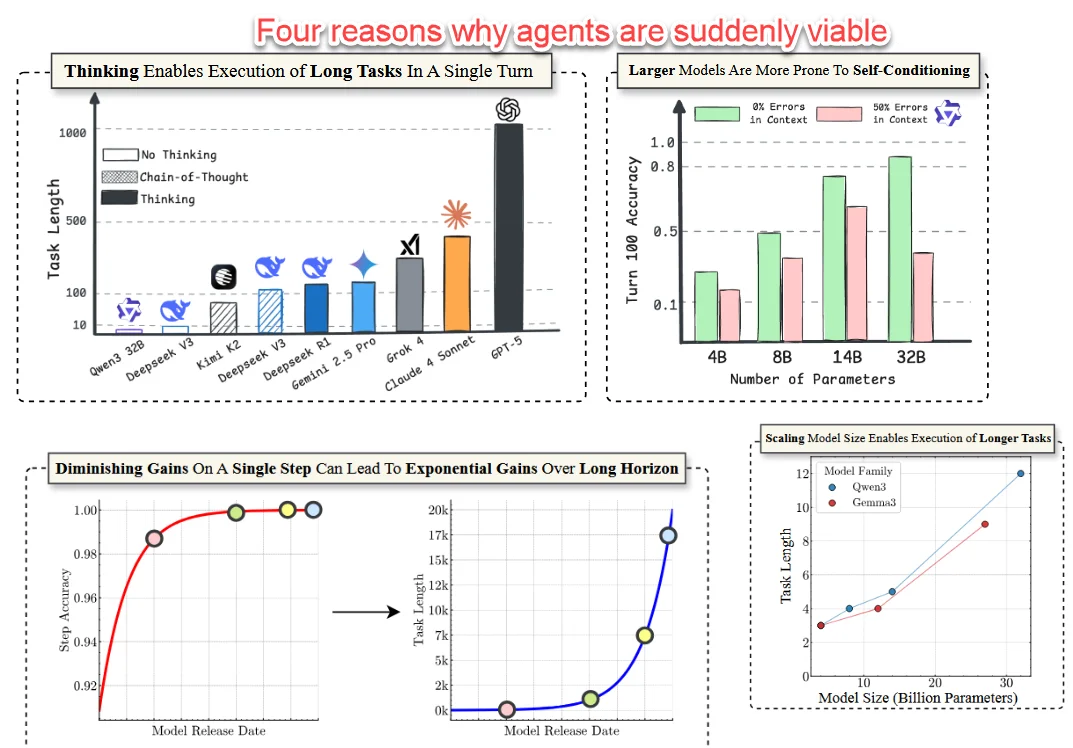

As artificial intelligence continues to get better, the gap between man and machine has narrowed. In numerous domains, AI have either caught up to human capabilities or bettered them. You might ask me what’s my evidence for making such grandiose claims. Here are some charts:

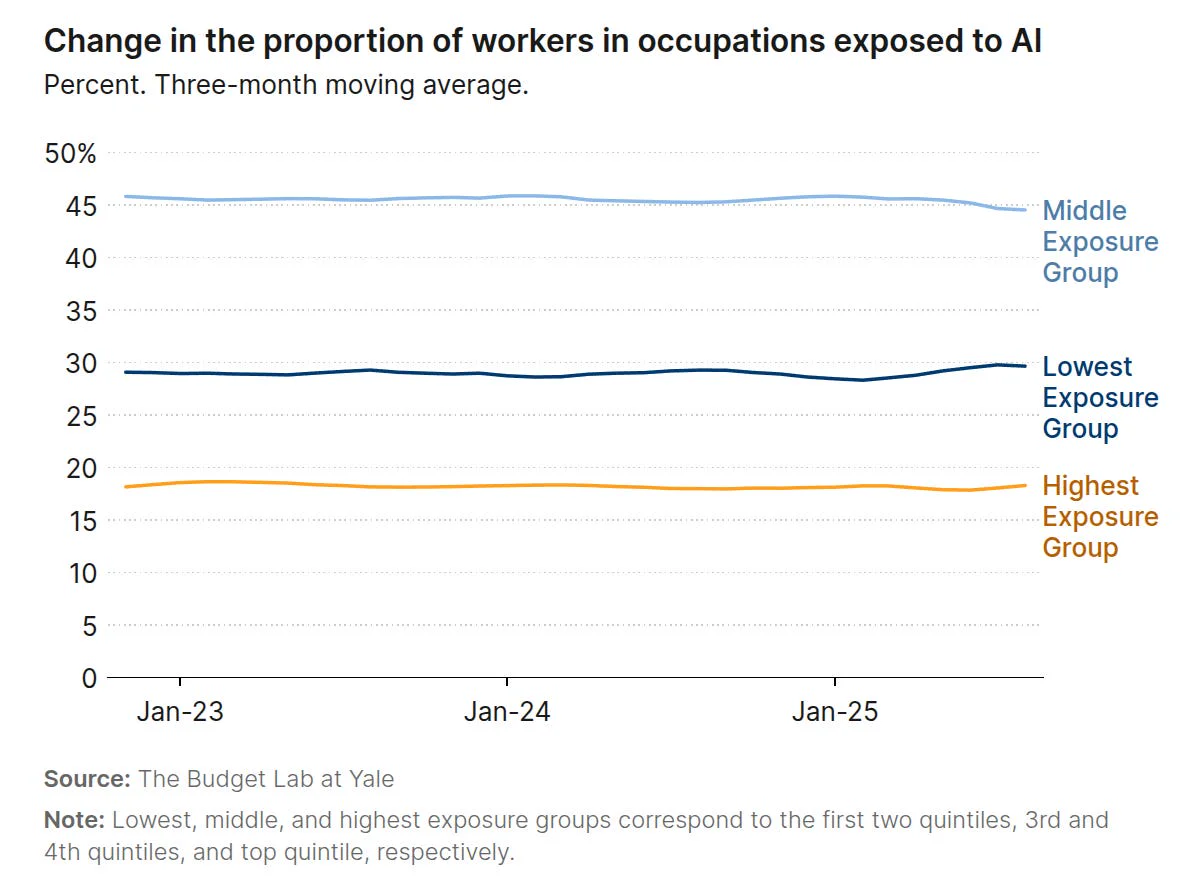

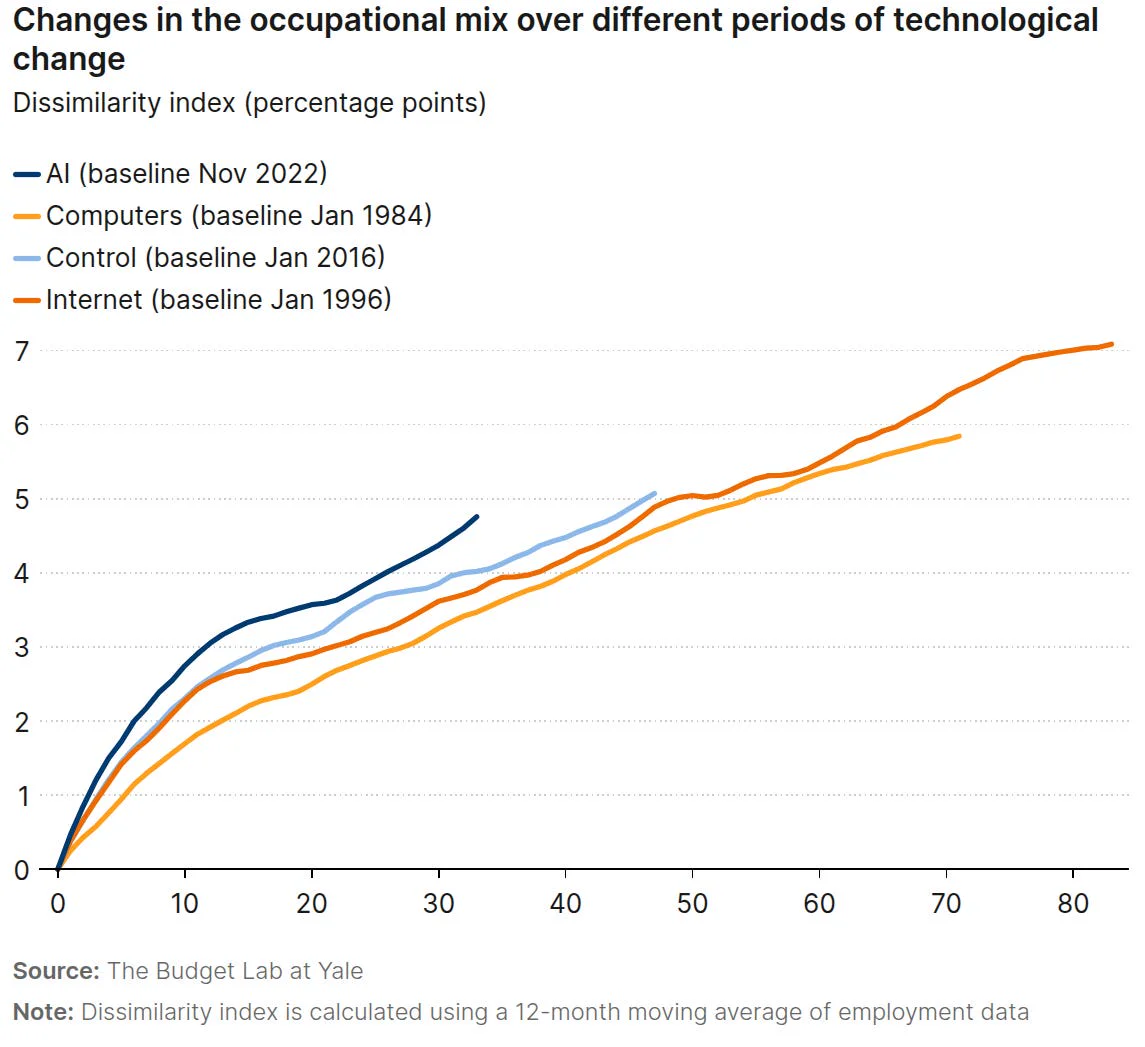

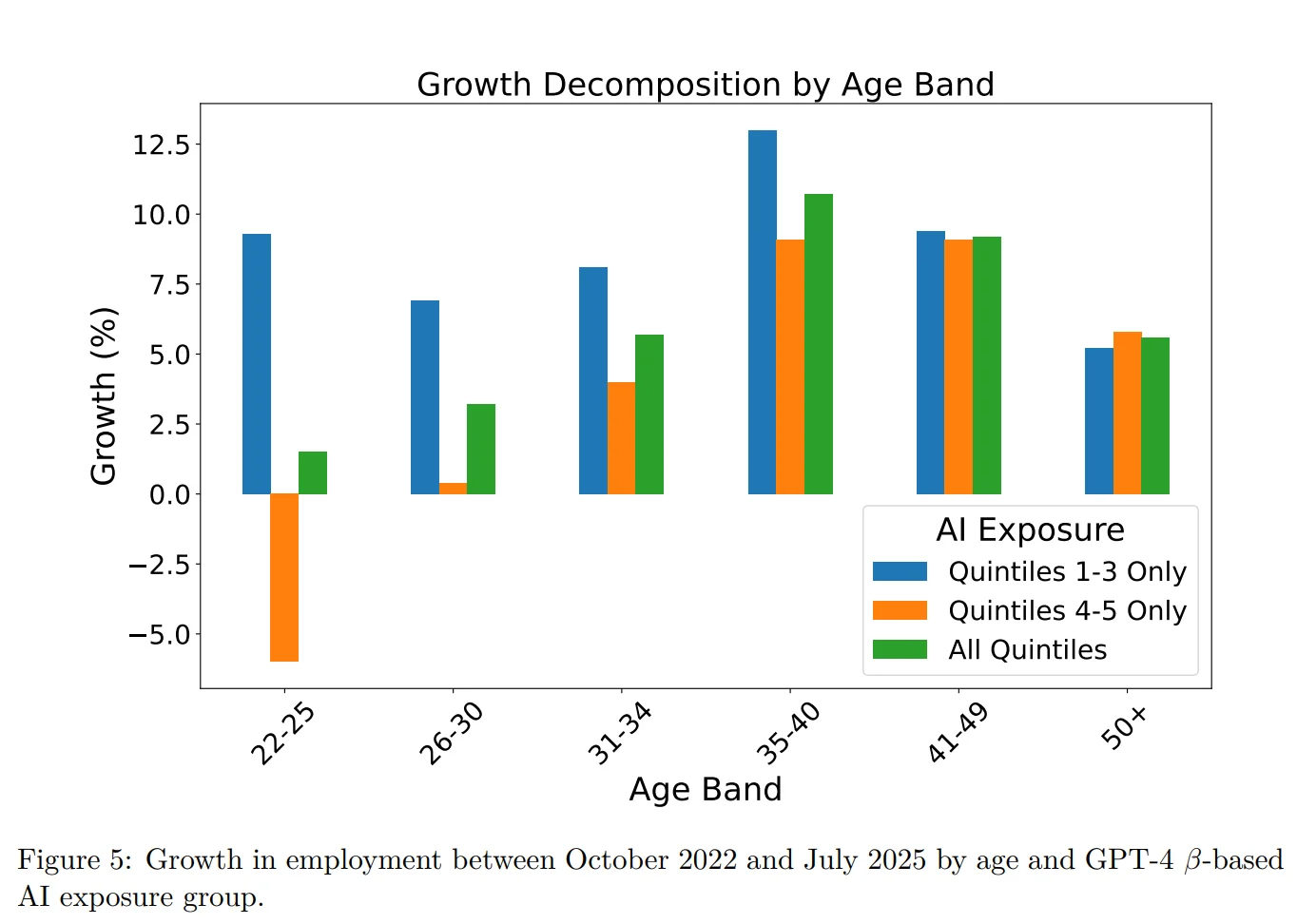

One can reasonably say that these benchmark charts are useless and that what ultimately matters is whether AI is actually eliminating jobs. On that question, the data is contradictory. For example, here’s data from a recent study by Brookings and Yale Budget Lab on how AI has affected the labor market in the US:

Generative AI has followed a similar trajectory in its first few years. We compared the pace of occupational change since ChatGPT’s launch to similar periods of change following the introduction of computers and the internet. We found that the occupational mix has changed marginally faster during the early ChatGPT era compared to previous technological shifts. However, these changes predate ChatGPT’s launch, suggesting AI may not be the primary driver.

Here’s a study by Brynjolfsson et al. (2025) showing how AI is affecting young workers with jobs highly exposed to AI. Paradoxically, other cohorts with jobs exposed to AI have not been affected.

Looking at all the graphs above, you can reasonably object saying that benchmarks are flawed and no benchmark can reflect the true complexity of a real world task.

That’s a fair objection.

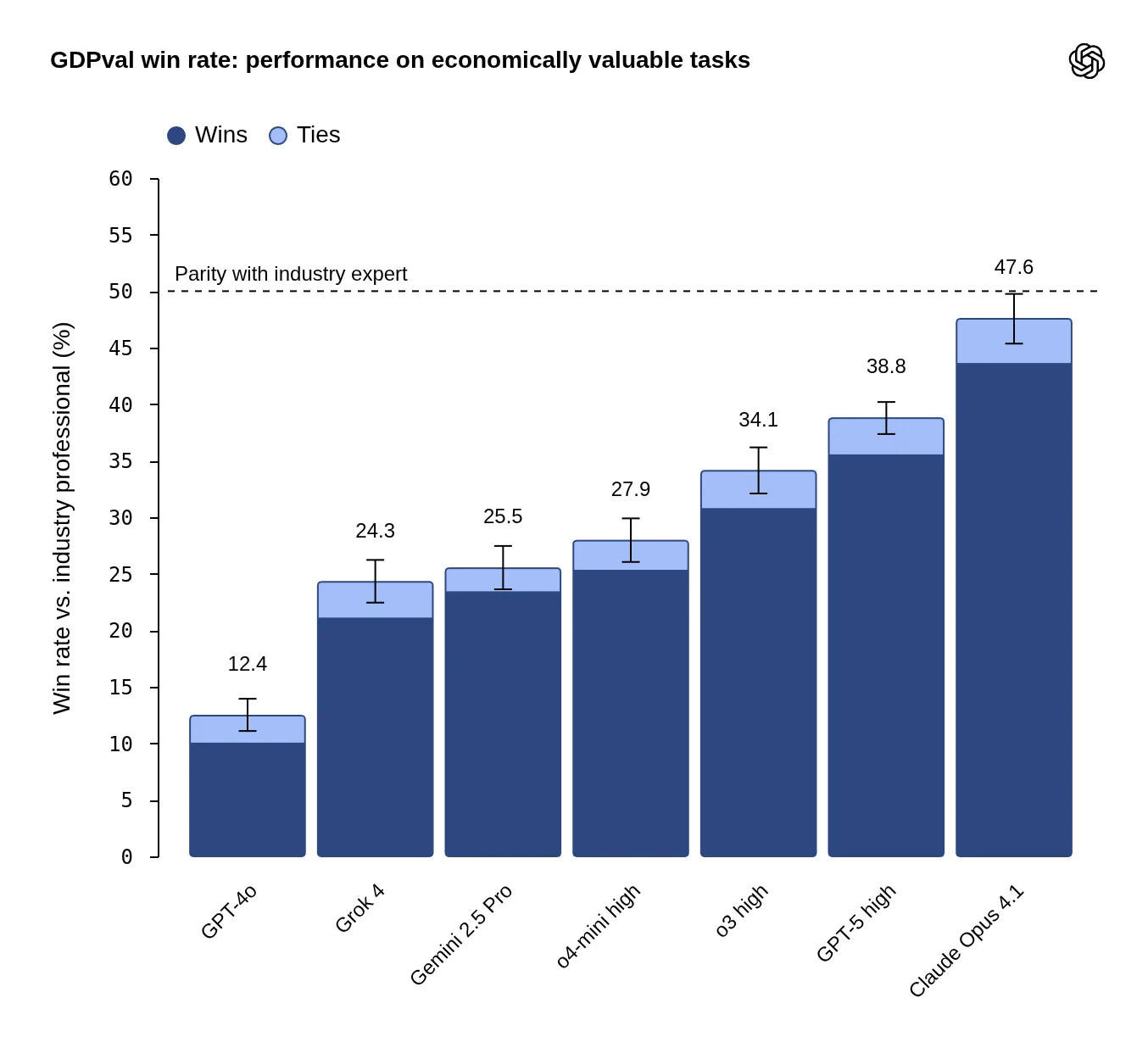

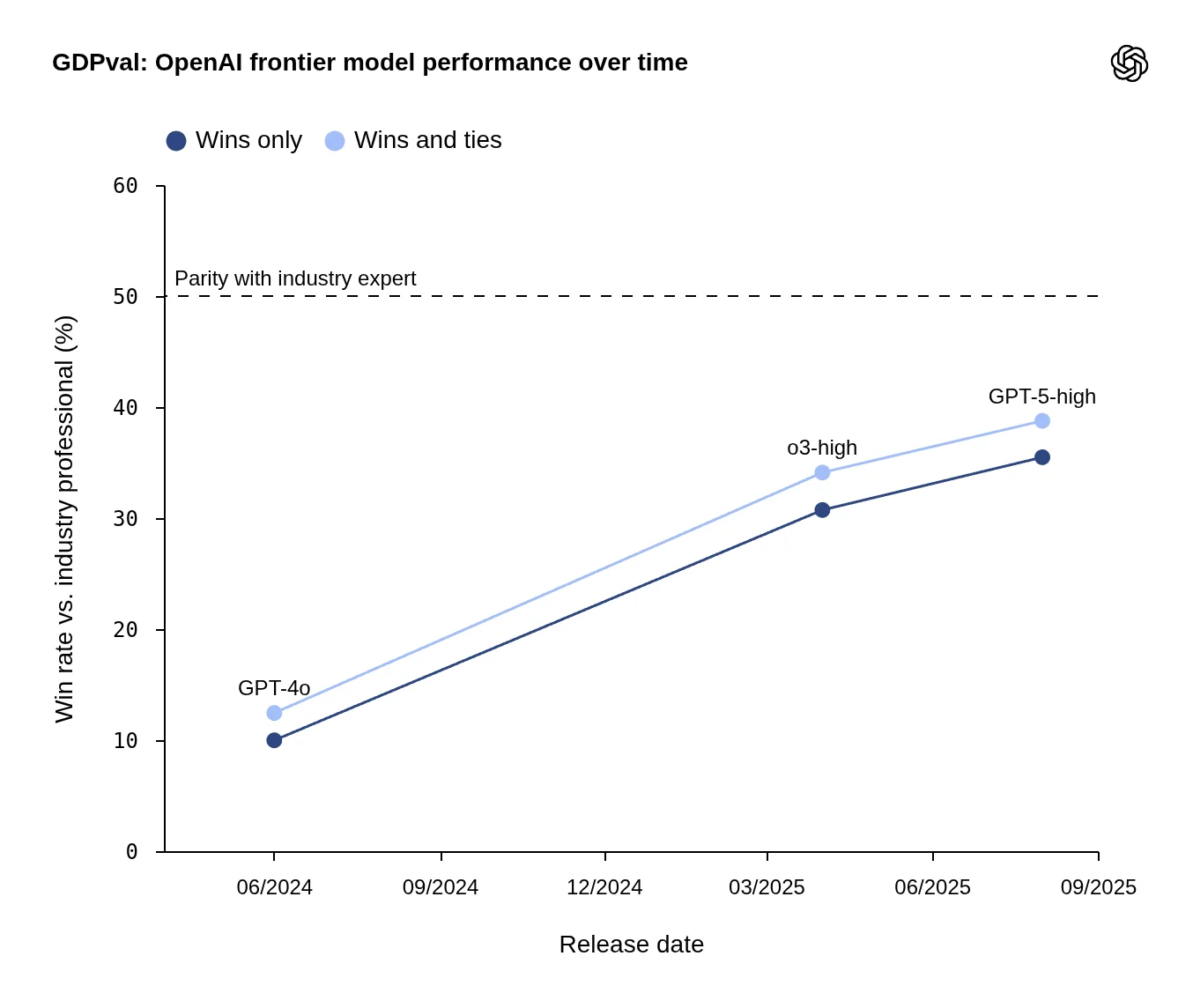

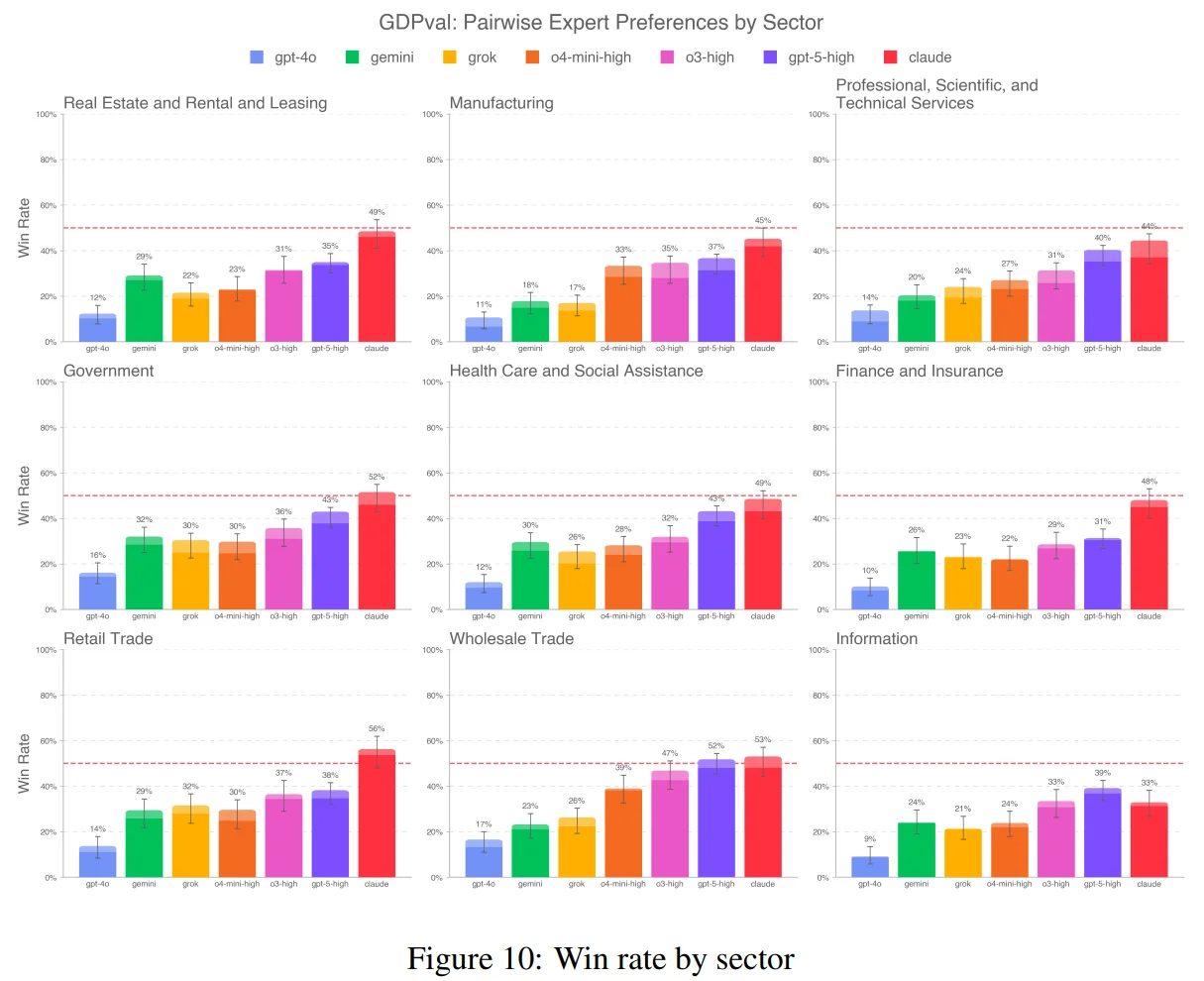

To bridge this gap between benchmark tests and the complexity of real-world tasks, OpenAI ran a study where they recruited experts with an average experience of 14 years from a variety of fields like real estate, manufacturing, professional services, health care, and finance to design real world tasks with real deliverables and evaluate the performance of large language models (LLMs).

The results are either sobering or exciting depending on whether you are an AI boomer or doomer. Frontier models are approaching industry-expert quality in terms of the work output quality.

Despite the flaws in the design of the study, at this moment, I’m in the camp that AI models will soon better humans in a vast range of tasks. I also think this is inevitable, even if AI progress were to dramatically slow down. This is my current prior based on the best available evidence, anecdotes and generous linear extrapolation and I’ll update it when I come across evidence that disproves my prior.

Before I say anything, I want to be clear what I mean by AI. When I say AI, I don’t mean some sentient godlike technological entity that is all seeing, all knowing, and can do anything.

No.

At this stage, when I say AI, I am talking about large language models like ChatGPT and Claude. Those median statistical bullshitters that we all so love-hatingly use every day.

Writing in the Free Press, economist Tyler Cowen and Anthropic Chief of Staff Avital Balwit frame the defining question of our time:

We stand at the threshold of perhaps the most profound identity crisis humanity has ever faced. As AI systems increasingly match or exceed our cognitive abilities, we’re witnessing the twilight of human intellectual supremacy—a position we’ve held unchallenged for our entire existence. This transformation won’t arrive in some distant future; it’s unfolding now, reshaping not just our economy but our very understanding of what it means to be human beings.

Nearly 2500 years ago, Greek philosopher Socrates said “the unexamined life is not worth living” and exhorted his fellow Athenians to think critically about the life they lived. Today, as LLMs continue to get better, I think we all need to think about what it means to be human in a world where machines are better at most things, regardless of whether that reality comes to pass. This is not a simple question—its dimensions are vast and touch various aspects of our lives: what does it mean to work, learn, provide, create, share and perhaps most importantly, what’s one’s place in the world.

If you are thinking that this idiot is being unnecessarily melodramatic or causing petty panic, think about how far we have come since 2022 when ChatGPT launched:

In 2021 you had to Google to find something.

In 2025 the collective knowledge of humanity is a prompt away.

I don’t know about you, but that’s wild to me.

Me asking you to think about these hard questions has nothing to do with the impending arrival of artificial general intelligence (AGI) or artificial super intelligence (ASI) or some other imagined sci-fi future.

No.

I think that even if progress on LLMs stops today, vast swathes of knowledge work and bullshit jobs can be automated away and that doesn’t bode well for society.

The time to be pessimistic is now!

Set aside your views on whether you think LLMs are good or if they are just regurgitators of the median mediocrity of humans. One of the hallmarks of being intellectually rigorous is to think critically about the range of potential future outcomes. Engaging in this visualization doesn’t help you predict things but it helps you shrink the space for surprises and force you to prepare for whatever comes. You can’t predict but you can prepare and that’s the best we all can hope for.

As LLMs continue to get better, they are encroaching on things that give humans meaning in life. With each model update, the question of what it means to be human in an age of machine intelligence is getting harder and harder to answer.

I don’t know if LLMs will continue to get better at the same exponential rate. As things stand today, they are pretty close to human capabilities in many areas. I think it’s time for all of us to think about a future in which they are better than us at most things, if not all things, regardless of whether that will come true or not.

Even if LLMs can’t do what you can do today, there’s a non-trivial probability that they soon might. Here I’ll be honest and admit that I am making that assertion based on simple linear extrapolation.

You might think that I’m an innumerate idiot but my model is still better than most experts as AI researcher Julian Schrittwieser pointed out in a recent blog.

Bullshit jobs

I started reading Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber a week ago and here’s an excerpt from the preface:

But rather than allowing a massive reduction of working hours to free the world’s population to pursue their own projects, pleasures, visions, and ideas, we have seen the ballooning not even so much of the “service” sector as of the administrative sector, up to and including the creation of whole new industries like financial services or telemarketing, or the unprecedented expansion of sectors like corporate law, academic and health administration, human resources, and public relations.

And these numbers do not even reflect all those people whose job is to provide administrative, technical, or security support for these industries, or, for that matter, the whole host of ancillary industries (dog washers, all-night pizza deliverymen) that only exist because everyone else is spending so much of their time working in all the other ones.

These are what I propose to call “bullshit jobs.” It’s as if someone were out there making up pointless jobs just for the sake of keeping us all working.

Jobs like administrative tasks, report generation, sending emails, scheduling, basic data analysis, corporate communications and the like are classic examples of bullshit jobs. If there was ever a category of jobs tailor-made to be automated by LLMs, it’s bullshit jobs.

Nobody wants to think that their jobs are bullshit no matter how true it is. A corporate communications manager doesn’t wake up thinking “I do meaningless work.” They have a title, a salary, a sense of purpose, and a place in the social hierarchy. Their identity is wrapped up in that job, bullshit or not.

Ok, now assume I am right and think for a second what would happen to your sense of what it means to be a productive human if these bullshit jobs were to vanish. Most people not only underestimate the number of bullshit jobs out there but also delude themselves into thinking their job isn’t one. But I think deep down, a lot of people know that their jobs are bullshit jobs. All it takes is a couple of drinks for them to admit.

So when I say LLMs can automate bullshit jobs, I’m not celebrating the liberation of human potential. It’s frankly depressing given that millions of jobs fall under this category. I’m scared that they are ripe for being taken over by LLMs and most people are oblivious to this risk. What this does to people’s sense of self is a depressing question to ponder. If LLMs can do the bullshit jobs—the rote, administrative, box-checking work—what makes you think they can’t eventually do the meaningful knowledge work too?

Now put your hand on your heart and ask yourself these questions:

-

Is your job a bullshit job?

-

If it’s not, how long do you think you have before an LLM can do it better than you can?

I can immediately imagine a person of great purpose leaping like a Leopard to mentally kick me in the proverbial nutsack and educate me with the following factoids:

-

Every generation thinks that big technological shifts are disruptive. From electricity, cars, computers, to the internet, people have been screaming this time is different for ages.

-

New technologies always create more jobs than they destroy. Automation creates adjacent opportunities we can’t even imagine yet. For example look at all the internet industries created by the internet that nobody predicted.

-

LLMs are just sophisticated autocomplete. They can’t do physical labor, can’t think strategically, and lack true understanding. They’re tools, not replacements.

-

This is a bubble. Remember the dot-com crash? Everyone thought the internet would change everything overnight. The hype will die down and we’ll realize AI is just another tool.

-

Scaling has clearly hit a wall. They’re running out of data, running out of compute, and the improvements are plateauing. This exponential growth narrative is falling apart.

-

Humans will always be needed in the loop. You can’t just deploy AI without human oversight, judgment, and accountability. Regulations alone will slow adoption to a crawl.

-

AI hallucinates constantly and makes stupid mistakes. No company will trust mission-critical work to something that confidently tells you 2+2=5.

-

We’ll adapt like we always have. Humans are resilient. New forms of work will emerge. Society has survived every technological disruption and this won’t be different.

Scott Alexander captures why these conversations go so badly in a brilliant post:

Some people give an example of a past prediction failing, as if this were proof that all predictions must always fail, and get flabbergasted and confused if you remind them that other past predictions have succeeded.

Why do these discussions go so badly? I am usually against psychoanalyzing my opponents, but I will ask forgiveness of the rationalist saints and present a theory.

I think it’s because, if it’s true, it changes everything. But it’s not obviously true, and it would be inconvenient for it to change everything. Therefore, it must not be true.

And since most people refuse to use this snappy and elegant formulation, they search for the closest thing in reasoning-space that feels like it gets at this justification, and end up with things like “well you need to prove all of your statements mathematically”.

I could argue that AI isn’t a narrow technology like electricity and that it can replace cognitive tasks at scale or that its possibilities are limited only by human imagination or that this time can be different but leave that aside.

What I am asking you to do is to imagine for a moment that most, if not all the predictions about AI are true. What will that do to your sense of what it means to be a human in this world?

Who are you without a job?

Let me re-frame that question. Today, for better or worse, most people’s identity is deeply tied to the work they do. The most terrifying question for a lot of people is “who are you outside your job?”

But a job is about far more than income or identity, as important as those are. A job is a societal marker and signals if a person is a productive member of society. Employment status affects everything from visa applications to mortgage approvals. In countries without universal healthcare, losing one’s job can mean losing health insurance. Even where benefits exist, employment determines one’s access to credit, housing, and social standing.

Jobs structure the entire architecture of a person’s life. A lot of people meet their romantic partners at work. Having a job also influences a person’s decision to get married, have kids, buy a house, and the choice of where to live. A job isn’t just what someone does from 9 to 5—it’s the organizing principle around which modern life is built. It shapes one’s conception of the present and the future.

Now, assume that there’s a very real threat that LLMs can automate entire swathes of jobs and other AI advancements—if and when they happen—can make this worse. If AI does become really good, what happens to the broken identities of people? What happens when the organizing principle of society simply… vanishes?

Regardless of what your view about AI is, if you aren’t thinking about this question, you are not being intellectually honest. You are just burying your head in the sand and hoping for the best.

Let me be clear: I have no idea if AI will continue its current rate of progress and how it will affect the world, whether it will automate a lot of jobs. Neither does anyone. I also don’t want to be misunderstood as predicting the wholesale collapse of society. This is why I half-jokingly coined Bhuvan’s law and it applies to everything I’ve said so far:

“Any discourse about artificial intelligence is indistinguishable from talking out of your ass.”

It could very well be that most people like me are thinking about the downsides of AI and not enough about the upside because of loss aversion but nobody knows what tomorrow holds except for two people—god and a liar. AI could very well turn out to be a bubble like crypto, railroads or the dot-com bubble. It could also just unleash a brave new world that leads to the flourishing of the human race or it could turn out to be a dud. What possibility would you bet on?

When the future is uncertain, the least you can do is to visualize the potential futures both good and bad. There’s no point in thinking about the worst when you are dealing with small scale changes but that’s not the case today. The fact that LLMs (even before “more advanced AI”) can do so many things shows that we are dealing with a paradigm shift and not an incremental change.

If the paradigm shift threatens to shatter all conceptions you have about what it means to be human, how can you avoid thinking about the hard question, which is what does it mean to be a person in the shadow of AI?

The time to imagine the worst is now

This brings us back to the Stoics. Premeditatio malorum wasn’t about pessimism or doom-mongering. It was about mental preparation. By imagining loss, hardship, and change, the Stoics built psychological resilience. They didn’t predict the future—they prepared for multiple versions of it.

That’s what I’m asking you to do. Not to panic, not to despair, but to sit with the uncomfortable questions:

-

If your job disappeared tomorrow, who would you be?

-

If machines could do most cognitive work, what would give your life meaning?

-

If work is no longer the primary organizing principle of society, what comes next?

These aren’t hypotheticals from some distant sci-fi future. These are questions you should be wrestling with now, because the answers will shape how you navigate the next decade.

The Stoics understood something fundamental: you can’t control what happens to you, but you can control how prepared you are to face it. You can’t stop AI from advancing. You can’t prevent the disruption that’s coming. But you can do the hard work of imagining what that disruption looks like, and you can start asking yourself the questions that matter.

Because when the future arrives—and it will—the people who’ve done this work won’t be caught flat-footed. They’ll have already wrestled with their fears, examined their identities, and thought deeply about what it means to be human when machines can think.

That’s not pessimism. That’s preparation.

The worst case is that this entire thing becomes a pointless thought excerisise. What do you have to lose?

Image: Claude Monet: Gare Saint-Lazare, 1877, National Gallery