I have an embarrassing and pretentious-sounding confession. One of the reasons why I created this blog is because I really enjoy collecting links—the internet calls it “curation” nowadays. Boy, does it sound douchey just to use the term.

I don’t know why but I’ve always loved sharing interesting things with friends and colleagues. But over the years, an abundance of good things on the internet quickly went from a boon to a bane. There’s too much to read, watch and listen to but too little time. The side effect was FOMO. We kept collecting and saving more and more things that we’d never go back and read or watch.

This problem of overload kept coming up whenever I was talking to friends, colleagues or in some cases went talking to startups that approached Rainmatter.

One of the reasons for my fascination with curation is because some of my favorite blogs and newsletters on the interweb like Marginal Revolution by Tyler Cowen and Kottke by Jason Kottke, The Marginalian by Maria Popova, Techmeme, and Klement on Investing by Joachim Klement are curated—I love reading them.

The common theme among all these blogs is that all these people share things because they enjoy it and they don’t pander to the whims and fancies of audiences or algorithms. These writers are among the minority on the internet not yet infected by the disease of “engagement.” These blogs still have some of that magic of old-school blogging. The tragedy of our age just sharing interesting things without worrying about engagement or pandering to algorithms seems heretic.

Anyways, this problem of too much was stuck in my head and I figured, I’d put all the interesting things I came across in one place. That was how this blog was born and I’ve done a piss-poor job of doing what I wanted to so far. Then I figured, why not learn about “curation” and as I was browsing by Michael Bhaskararound I came across this Google talk by this person named Michael Bhaskar. It was really good. Turns out he had written a book on curation Curation: The power of selection in a world of excess.

I finished reading it last week and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Given just how huge the problem of abundance today is, I have a feeling that this book will become important and better with time—like wine.

By now talking and writing about information overload and the sheer excess of everything on the internet is a tired cliché but doesn’t make it any less true. We live in an age of excess—everything from amazing blogs, books, podcasts, newsletters, cheap Vietnamese clothing to terrible Kannada movies (The guy falls in love with the girl, father says no, stalker boyfriend beats hero, hero beats up the stalker, hero smiles, father cries, girl marries, flash-front, 2 kids). We have too much of every goddamn thing and it’s a pain in the hindquarters.

We generate 2.5 quintillion bytes or 2,500,000,000,000 megabytes of data every day—this factoid in the first chapter sets the stage for the rest of the book. The author presents a sweeping panorama of how we went from a world of scarcity to a world of abundance—everything from clothing to information.

How did humanity go from the problem of too little to too much? Bhaskar goes back to back to the 1700s to trace the origins of what he calls the long boom to innovators like Richard Arkwright, Emil Rathenaul, and Werner von Siemens.

Arkwright invented the spinning frame and the carding engine and is called the father of the Industrial Revolution and the modern factory system. Thanks, to his inventions the cost of a short went from $3500 (Yes, I was shocked too and yes, it’s true) to a few dollars today! Werner von Siemens invented the telegraph and the dynamo among other things and revolutionized communications and power generation supercharging industrial production.

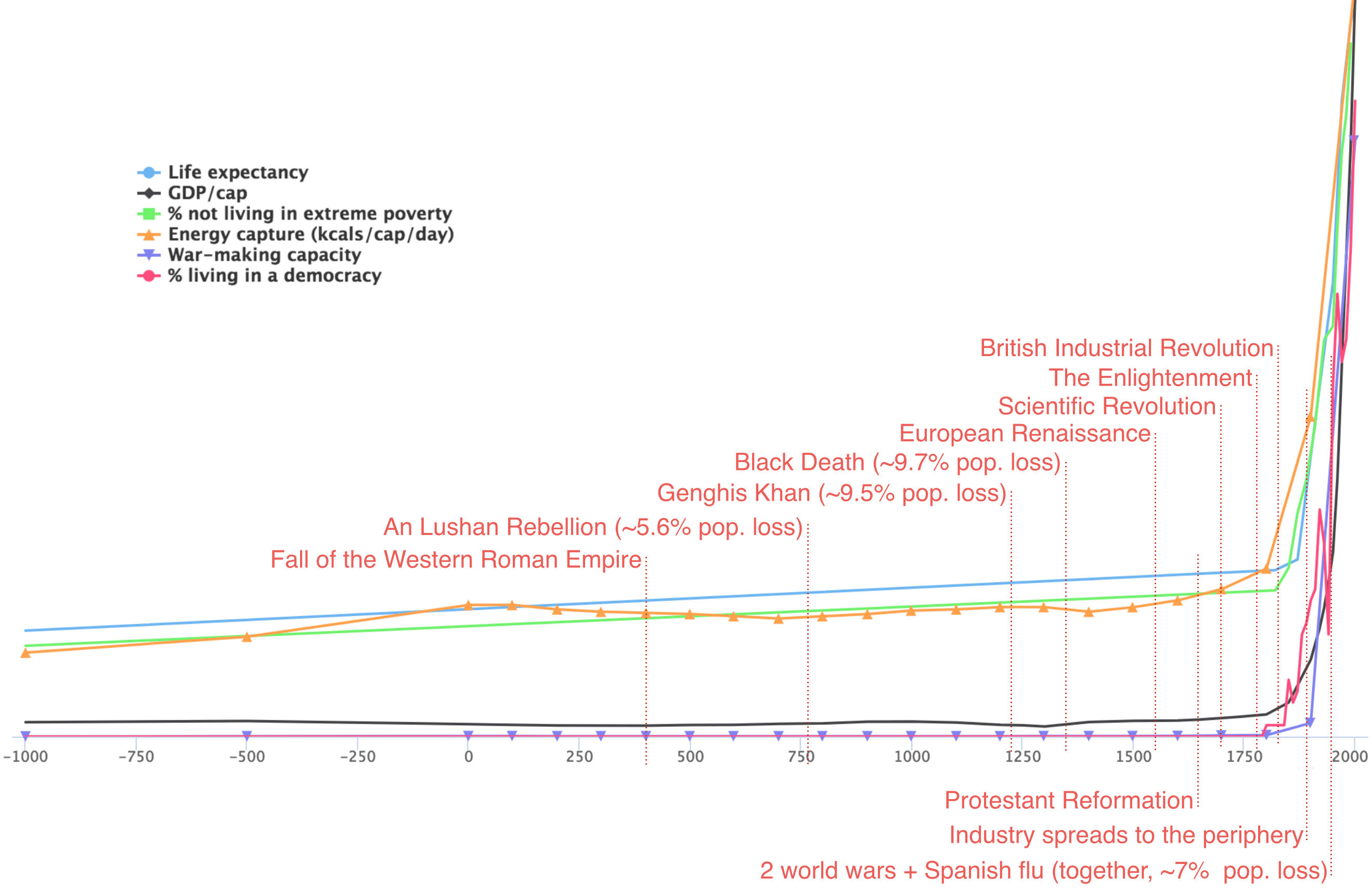

The short descriptions of these famous men are fascinating given that I know next to nothing about the industrial revolution except for the fact that I knew the industrial revolution happened thanks to my relentless mugging of social studies textbooks in school. The two industrial revolutions starting from the late 1700s to the early 1900s pushed humanity from an age of scarcity to abundance. This chart by Luke Muehlhauser illustrates the profound impact of the industrial revolution.

The big bang

The economy is an expression of its technologies

W. Brian Arthur

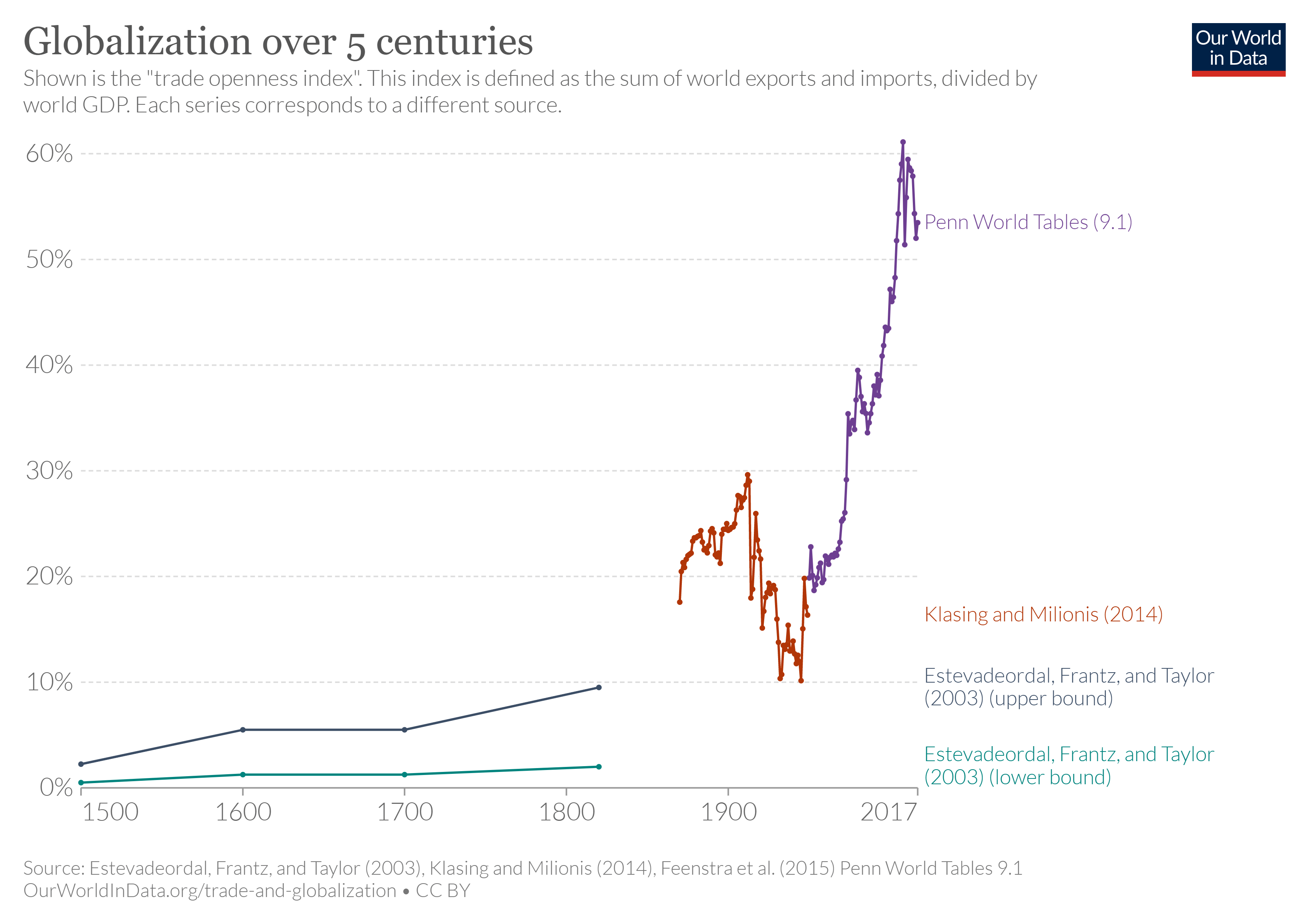

The technological advancements of the industrial revolution, two world wars set the stage for globalization but It didn’t happen immediately. Around the 1970s thanks to advancements in shipping and containerization, the world started to become a smaller place. Global trade started to take off but the biggest event that changed things was _China’s accessio_n into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 and global trade increased dramatically and everything became cheap.

The result was that we all became hoarders.

Who are some of the greatest philosophers you can think of? You might probably be thinking old Greek and Roman guys like Plato, Artistotle and other brand ambassadors for arthritis medication. But if you ask me, George Carlin is one of the greatest philosophers of our time. There was nobody who observed all the dumb things we do better than him. Just watch these two videos:

Thanks to the industrial revolution and the wartime technological advancements we quickly went from not having the things we needed to filling our houses with things we don’t need and paying for it with money we don’t have—buy now, pay never!

What Charles Dickens wrote over a century ago is a perfect summary of today:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.

Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

Globalization enabled unchecked consumerism and our homes became glorified storage containers. Too much of everything.

Novelty and excess become the norm and no longer excite us. Moreover, all this wealth increases pressure to keep up with the Joneses. Your Ford, impressive enough last year, loses its lustre now your neighbour owns a Mercedes.

Curation: The power of selection in a world of excess—Michael Bhaskar

Here are some numbers from Life at Home in the Twenty-first Century study by UCLA. Bhaskar quotes the study in the book too:

In the smallest home in their study, a house of 980 sq ft, there were, in the two bedrooms and living room alone, 2,260 items. And, because of the rules the anthropologists were using to count, that was only the things they could see when they stood still. They didn't count any of the stuff that was tucked into drawers or squeezed into cupboards.

The other homes were just as packed. On average, each family had 39 pairs of shoes, 90 DVDs or videos, 139 toys, 212 CDs and 438 books and magazines. Nine out of 10 had so many things that they kept household stuff in the garage. Three quarters of them had so much stuff in there, there was no room left for cars.

Globalization enabled unchecked consumerism and our homes became glorified storage containers. Too much of everything. Now, we’re all mindless shoppers constantly buying things. You could probably spin that and say you’re contributing to India’s GDP but, your family might not like the explanation.

For Earth to the metaverse, we’re all hoarders

It’s not just too much physical stuff, there’s too much digital stuff too. Just some stats:

-

About 1 million books are published every year.

-

Over 500 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute.

-

500 million tweets a day

-

5-10 million blogposts are published every day

-

80-100 million photos and vidoes are uploaded on Instagram every day.

-

Spotify has over 86 million songs and 3.6 million podcast episodes.

If you check Internetstats, there’s a non-trivial chance of you losing your mind. This is what people mean when they say there’s information overload.

So, everybody agrees that we have information overload?

In the immortal words of every bickering couple “well, not quite.”

The way I see it, there are three viewpoints. The dominant view, of course, is that there’s too much information and people are losing their minds.

‘We live in an age of electricity, of railways, of gas, and of velocity in thought and action. In the course of one brief month more impressions are conveyed to our brains than reached those of our ancestors in the course of years, and our mentalising machines are called upon for a greater amount of fabric than was required of our grandfathers in the course of a lifetime.’

Curation: The power of selection in a world of excess—Michael Bhaskar

People like Daniel Levitin (neuroscientist) fall into this camp:

Americans took in five times as much information every year every day during this year and we did in 1987. Five times as much information every single day we take in the equivalent of a 175 newspapers read cover to cover. In our leisure time alone we processed 35 gigabytes of information, that's the equivalent of 5 high-definition DVDs in a day in our leisure time we created a world that has 300 exabytes of information.

If you were to write each bit of information on a little 3 by 5 card like this, just your share your individual share of that information, if you were to take those index cards and stack them they would reach from here to the moon and back and then to the moon again. 750 thousand miles is your share of the information created in the world.

The Organized Mind: Using Neuroscience to Navigate the Age of Information Overload

Then there are people like Clay Shirky and Tyler Cowen who think, it’s a problem of filtering rather than overload.

Clay Shirky:

I think this is and it goes back to the printing press right. Gutenberg and the invention of movable type injected for the first time into life outside universes information abundance right. By the 1500s the cost of producing a book had gotten so cheap and the volume of books being produced have gotten so large that an average literate citizen could have access to more books than they could read in a lifetime. So information overload is actually aproblem of fairly ancient provenance. Thinking about information overloadisn't actually describing the problem, and thinking about filter failure is.

It’s Not Information Overload. It’s Filter Failure, Clay Shirky

Tyler Cowen on information overload:

Google lengthens our attention spans in yet another way, namely by allowing greater specialization of knowledge. We don't have to spend as much time looking up various facts and we can focus on particular areas of interest, if only because general knowledge is so readily available. It's never been easier to wrap yourself up in a long-term intellectual project, yet without losing touch with the world around you.

As for information overload, it is you who chooses how much "stuff" you want to experience and how many small bits you want to put together. If you wish, you can keep information at bay as much as you need to and use Google or text a friend when you need to know something. That's not usually how it works—many of us are cramming.

The Age of the Infovore: Succeeding in the Information Economy Kindle Edition by Tyler Cowen

I used to be in the information overload camp but over time, I’ve slowly shifted to the filter failure camp. The more stuff—both physical and digital—we have to deal with, the better our filters have to be.

But as Bhaskar emphasizes multiple times in the book, it’s a good problem. Compared to a world of scarcity, a world of abundance is a much better place to be in.

Choice overload

MFs

We’re natural curators

For all the talk of the human brain being a supercomputer, the conscious brain is basically like a floppy disk. It’s our unconscious brain that ends up doing most of the heavy lifting. Here’s an excerpt from the book:

Information overload is commonly accepted. The question is not whether it exists (given that our conscious brain can process something like sixty bits at a time and the amount of information now available is such that each American consumed the equivalent of 175 newspapers per day in 2011.

So, even though our conscious brains are constantly bombarded with information, they process only a tiny bit of it. Put another way, whether you know it or not, our brains are naturally filtering or “curating” everything. Cue the eye roll!

The way I think about it, curation is much less an activity than a worldview. To me, this was the biggest takeaway from the book.

In the context of excess, curation isn’t just a buzzword. It makes sense of the world.

Curation: The power of selection in a world of excess—Michael Bhaskar

We are naturally wired to cull, sift, filter, arrange and curate everything from what we think, read, eat, smell to what we sense. In that sense, curation is just the conscious application of what our brains were evolutionarily hardwired to do.

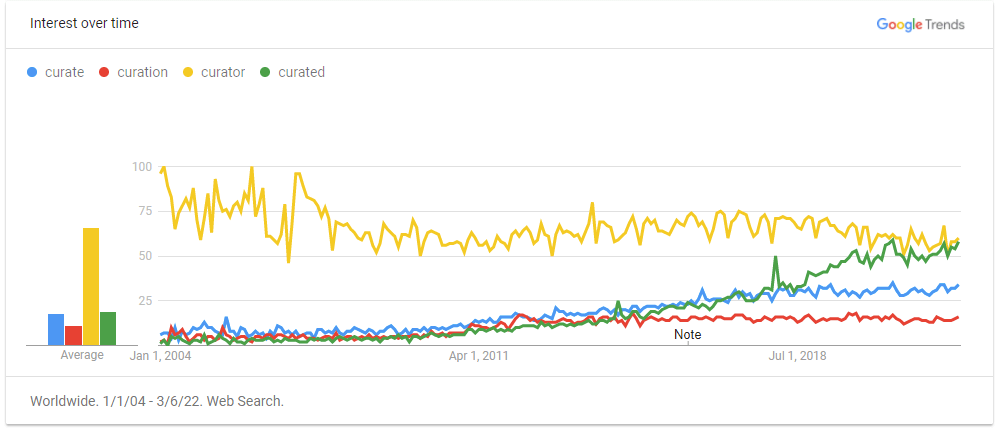

This leads to the debate over the use of the term curation and internet pissing contests over its appropriation. The term comes from the Latin word cūrāre, which means to look after or take care of. The term was originally used in the art and museum worlds but not that everybody is a curator, the art people are horrified.

But as Bhaskar writes in the book, what we call curation was already happening for ages and we just labeled those activities as curation. The term has always had an elitist undertone. Most often than not, you can sense the unbearable pretentiousness, pompousness snobbishness, and douchebaggery when people use the term callously. There’s a good chunk of the book dedicated to the fight over the usage of the term. But today, every jackass is a curator, and thanks to the relentless abuse, it kinda feels like the term is becoming a bit meaningless.

Some people like Choire Sicha, for example, really don’t like the overuse of the term to label trivial and banal actions as curation:

As a former actual curator, of like, actual art and whatnot, I think I’m fairly well positioned to say that you folks with your blog and your Tumblr and your whatever are not actually engaged in a practice of curation. Call it what you like: aggregating? Blogging? Choosing? Copyright infringing sometimes? But it’s not actually curation, or anything like it. Your faux TED talk is not going well for you if you are making some point about “curation” replacing “creation” because, well, for starters, “curation” is choosing among things that are created?

You Are Not a Curator, You Are Actually Just a Filthy Blogger—The Awl

But, as Bhaskar and Maria Popova say, the curated genie is out of the bottle:

Like any appropriated buzzword, the term “curation” has become nearly vacant of meaning. But, until we come up with a better one, it remains the semantic placeholder that best captures the central paradigm of Twitter as a conduit of discovery and direction for what is meaningful, interesting and relevant in the world.

What the hell does curation mean anyway?

Here’s how Micheal Bhaskar defines it:

Curation: using acts of selection and arrangement (but also refining, reducing, displaying, simplifying, presenting and explaining) to add value

Curation everywhere

One of the central arguments of the book is that making more things and adding more were solutions to most problems—but they may not be anymore.

First because for the last two hundred or so years we have engineered society and businesses to keep growing; to keep adding more. Second because we are now reaching overload, when incremental additions cause more harm than good. Lastly it is important as we have an idea, whether in business, the arts or our general lives, that creativity is always a net positive. Perhaps it is. If, however, problems arise from creating more, aren’t there grounds to question that assumption?

This is the underbelly of the creativity myth. The ‘growth complex’, perhaps. Just as creativity doesn’t have to be about quasi-divine newness, so growth can work differently. Growth can come from adding value, not adding more. Paradoxically, as the century wears on, we will realise that creating less, indeed, actively cutting down, leads to more prosperity.

This is true. The default answer to pretty much every societal problem or business problem has been to add more—build more things, add more features. This is partly because it was easier to do more than less.

The other thing is that we’re hardwired to think in additive terms to solve problems. Lediy Klotz, professor at the University of Virginia in a series of studies found that people instinctively overlook subtractive solutions to solve problems:

The paltry rate of subtraction in our organizational-improvement study was no fluke. We observed similarly low rates of subtraction across multiple tasks. To improve a redundant piece of writing, few participants produced an edit with fewer words. To improve a jam-packed travel itinerary, few removed events to allow them to savor the ones that remained. To improve a Lego structure, almost no one took pieces away. Whether people were changing ideas, situations, or objects, the dominant tendency was to do so by adding.

But there’s also the fact that thinking from the lens of doing less to do more is unnatural and contrarian. I think people would rather fail by doing more than less because they’ll have something to show. Maybe it’s a form of signalling, even? Because the virtues of working hard and doing something, even for the heck of it are deeply ingrained in our cultures. Doing less, one the other hand is the same as being lazy.

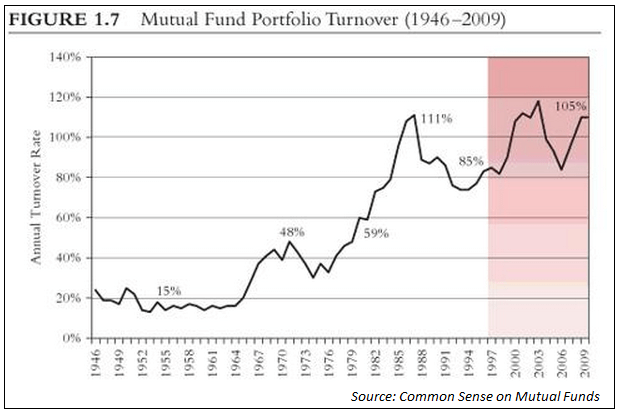

Then there’s career risk. Take fund management for example. The turnover rate of mutual funds across the much of the world has been going up. Take a look at this chart, this is for US funds, but it’s the same in India as well. A turnover rate of 100% means that the fund manager is changing the portfolio every year.

Of course, there are certain strategies like momentum that naturally have higher churn and some strategies that have higher churn to reduce risk maybe a good thing even. But not every fund is a momentum fund. In fact, there are more funds that have a value orientation (at least, that’s what they say) than other styles and value typically has very low churn. Most active mutual funds, don’t beat their benchmarks. Most investing requires the manager to hold on to stocks for a long time, but that’s also a sureshot way to bleed assets and get fired. Active managers doing Nothing? Unpossible!

So they have two choices:

- Hug the index and deliver predictable returns while spinning nice stories.

- Be seen as doing something. Trading just for the heck of it without any logic because in India, funds don’t pay taxes on churn. If you’re gonna take career risk, might as well go all-in.

The same applies to managers and CEOs as well. It’s better to be throw shit against a wall and see what sticks than be deliberate about what you do. This becomes even tougher when you have VC money because you then have external pressure to deliver performance. Companies often end up doing too many things and stretching themselves thin to appease investors than do more by doing less.

Running a business with a curation mindset requires being contrarian. This requires people to jettison some deeply ingrained values and beliefs. If there’s one bet I’d never take, it’s to bet against human inertia. It’s because of the human tendency to prefer doing nothing over something, that we’ll always prefer doing more, even if we know it’s futile.

Doing more with less is also at the heart of the “Degrowth” movement. The degrowthers like Jason Hickel argue that the only way to save our planet is to move away from an economic paradigm that prioritizes economic growth, production and consumption. That sound awfully like a more curated world. A world where people are more deliberate about the tradeoffs between growth and planetary wellbeing. But of course, degrowth has a lot of critics like Matt Klein and Branko Milanovic—not unlike critics of MMT.

Investing as curation?

There’s a nice section on Michael Moritz, the legendary partner at Sequoia who led investments in Google and PayPa on the parallels between investing and curation:

Moritz adjusted his companies to the reality as he saw it. He realised that you shouldn’t just select the right start-up, you then needed to continuously mould, adjust, rearrange it for reality, for constant change. You didn’t just invest in Google, you worked with the company to help it become Google.

Moritz resembles a curator as much as an old-style investor. The skills involved substantially overlap. In a complex scenario he found a new way of doing business that reacted to change. It’s a skill replicated by the best investors like Warren Buffett. Moritz claims it’s hard to find new VCs. It’s an exceptional skill set of selecting and arranging that is not easily replicable.Moritz adjusted his companies to the reality as he saw it. He realised that you shouldn’t just select the right start-up, you then needed to continuously mould, adjust, rearrange it for reality, for constant change. You didn’t just invest in Google, you worked with the company to help it become Google.

Curation: The power of selection in a world of excess—Michael Bhaskar

Is curation a cure for all ills?

If you read the book, you might get a feeling that curation is a solution to mos problem, eventhough the author takes great pains to say that it isn’t—it’s one tool in our toolkit. Curation isn’t just human, it could be algorthmic too. There are brillaint examples of algorithmic cuaration and human curation in the book. Here’s a quote from the book that was stuck in my head. It’s of Brian Armstrong, the co-founder of canopy.co speaking to Bhaskar:

We’ve only seen the very beginning of machine-driven curation – it’s still super-early in the game. People have been hand-picking things for thousands of years in their homes and shops, so human curation has a huge head start. Even though it’s becoming more and more pervasive, algorithmic curation is not yet a solved problem. Algorithmic curation will definitely get better, but it won’t ever have discerning taste or a unique point of view.

Brian Armstrong, Canopy | Curation: The power of selection in a world of excess—Michael Bhaskar

Curation really does help make sense of this world of excess. But we need to be equally wary of the side effects. Algorithmic curation on it’s own doesn’t work. In fact, except for Amazon to an extent it sucks. There’s an interesting example contrasting Apple App Store which has human curators behind the scenes and Android Apple Store which is algorithmically curated. The bottom line is that Android Store sucks.

But the way I think about it, there are some side effects too, especially on the internet.

I’m still a little hesitant to call myself a “curator” when the job of an actual curator involves touching the Monalisa. But like the author says in the book, the term is now a victim of mainstream appropriation and we have to make our peace with it.

Human brain natural curation

Deepstash, Morozov, crypto syllabus, DJ Taptu

A guy asking your interest

Awl

Pocket and it’s curation page. Instatpaper email My idea about a newsletter curated to your tastes

Curation and Trust Context-stripping – everything isn’t curation Collecting, filtering, sifting

Tastemakers -Seth godin

Curation is a business model Present in the middle ages just had enough information equivalent to a newspaper compared to today where we get on 75 years papers We’re all curators – signalling Good curation – value. Bad Big tech curation – Amazon, Spotify, Netflix apple curation-slcoal.media outrage

Now that I have read the book I see curation everywhere in fact my next book which I unknowingly pic as soon as I finished reading curation on my Kindle and this is a physical book was 50 economics classics by Tom butler Bowden. The book is a distillation of 50 of the biggest economic ideas from a variety of authors ranging from liyakat Ahmed friedman drucker polony samuelson schumpeter to Amartya Sen and Max Weber. Somebody who’s very interested in the dismal science of of economics and the snake study and astrology of micro masturbation I probably wouldn’t have studied all the ideas that having distilled of the famous economist in the book but he has done a brilliant job of summarising some of the biggest economic ideas that are enough to give an additive science to my world view of how I see the markets and economics given that either work in the financial services industry.

I have a feeling that this book of this book will become more popular as time goes on

One of the risksis that in a world started for context, any activity that is stripping, culling, summarising, will be seen a net negative. Context stripping maybe be rebranded as curation. Brevity isn’t always good. Sometimes you need a muddled mess because somethings sometimes are just that –mudess messes.

Curator economy will probably be like the creator economy and the Gig Economy before that. 80/20

Attribution, credit, payments

Moreover

—