On March 10th, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), the 16th largest bank in the United States, collapsed. SVB was the bank of choice for US startups, faux libertarian tech bros, and VCs. As the bank was going under, there was a minor miracle. All the economists, policy wonks, semi-retired epidemiologists, anthropologists, futurists, and cultural archeologists on Twitter suddenly transformed into US banking experts.

Since I’m on the internet, with a Twitter account and a blog, I’m a preordained banking expert. As such, it’s my duty to comment on what went wrong with Silicon Valley Bank. Even though I am in Bangalore, I must write about what Jay Powell, Janet Yellen, and Joe Biden should do to stabilize the US banking system. Them’s the rules.

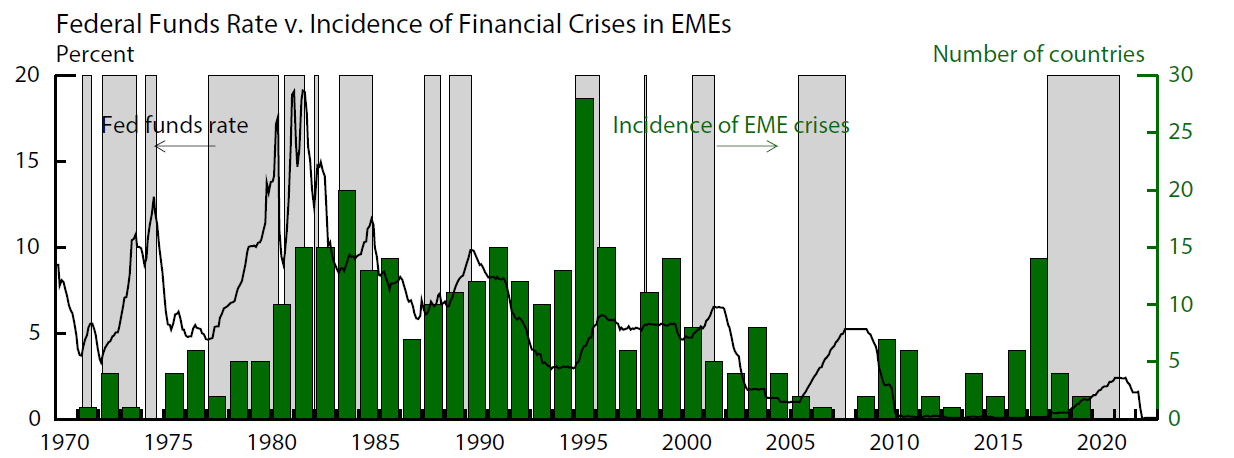

Throughout history, something broke whenever the Federal Reserve hiked rates [1, 2, 3, 4].

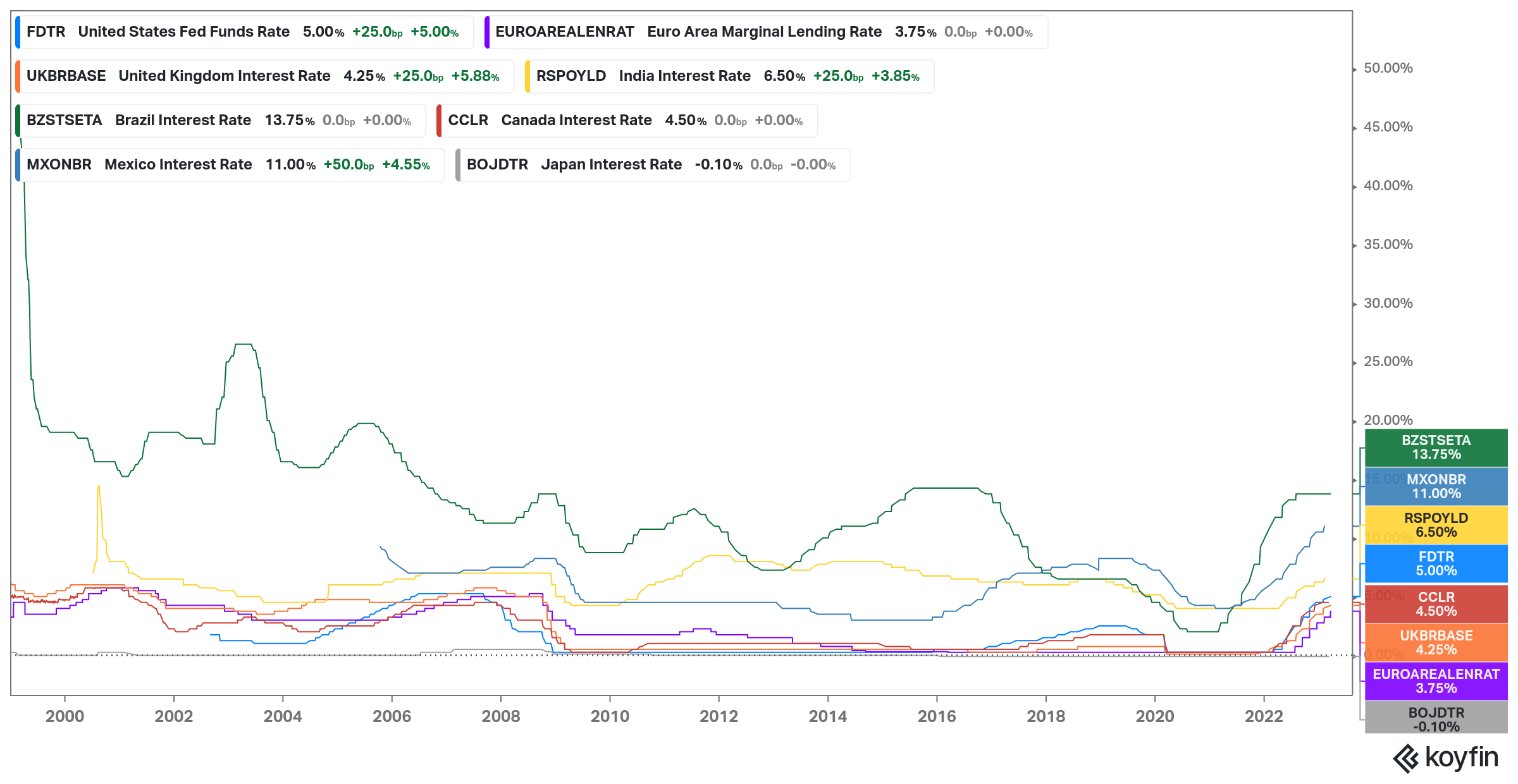

So when the Fed started hiking rates in 2022, the question on the minds of experts was, “Oh sh*t, what’s gonna break this time?”

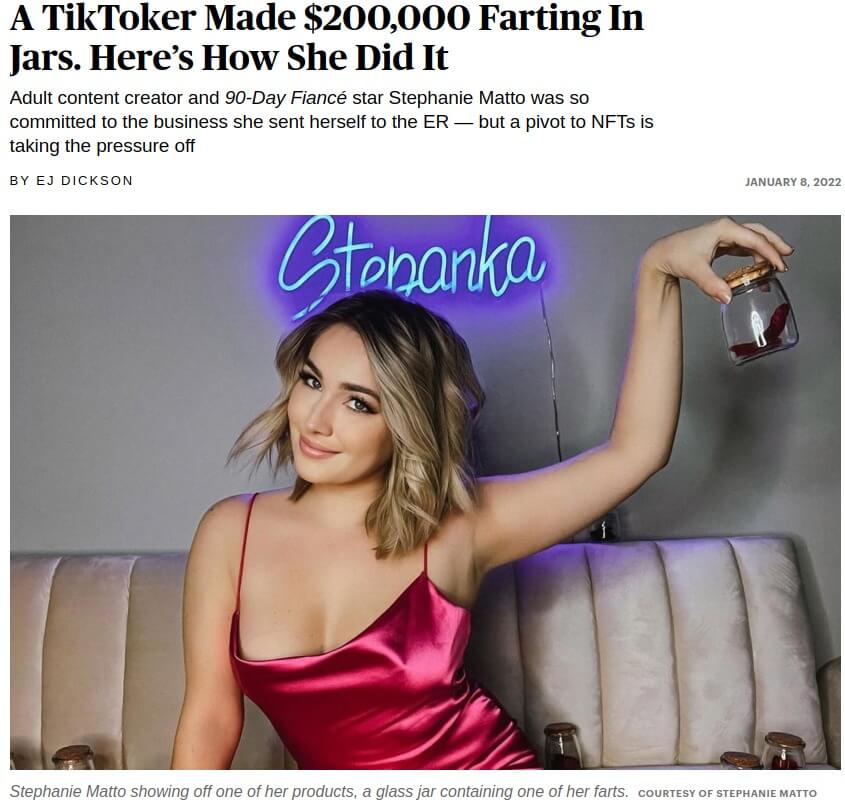

If you go back and look through the archives of IMF’s global financial stability reports, the biggest concerns were about rising sovereign and corporate debt, dollar-denominated debt in emerging economies, shadow banking, high asset price valuations, high real estate prices, non-bank leverage, private markets, and hot money flows. Policymakers were more worried about the prices of monkey pictures and bottled farts than banks.

In 2022, the biggest financial stability concern on people’s minds was the deteriorating liquidity in the US Treasury market, the most important bond market globally. If you had asked people in 2021 or 2022 if we would have a banking crisis in the future, they would’ve sent you Google search results for “de-addiction centers near me.” Except for the gold bugs and crypto crazies predicting the collapse of Western financialized civilizations for the past 30 years, there was almost a uniform consensus that banks in the advanced economies were safer post-2008 due to increased capital requirements.

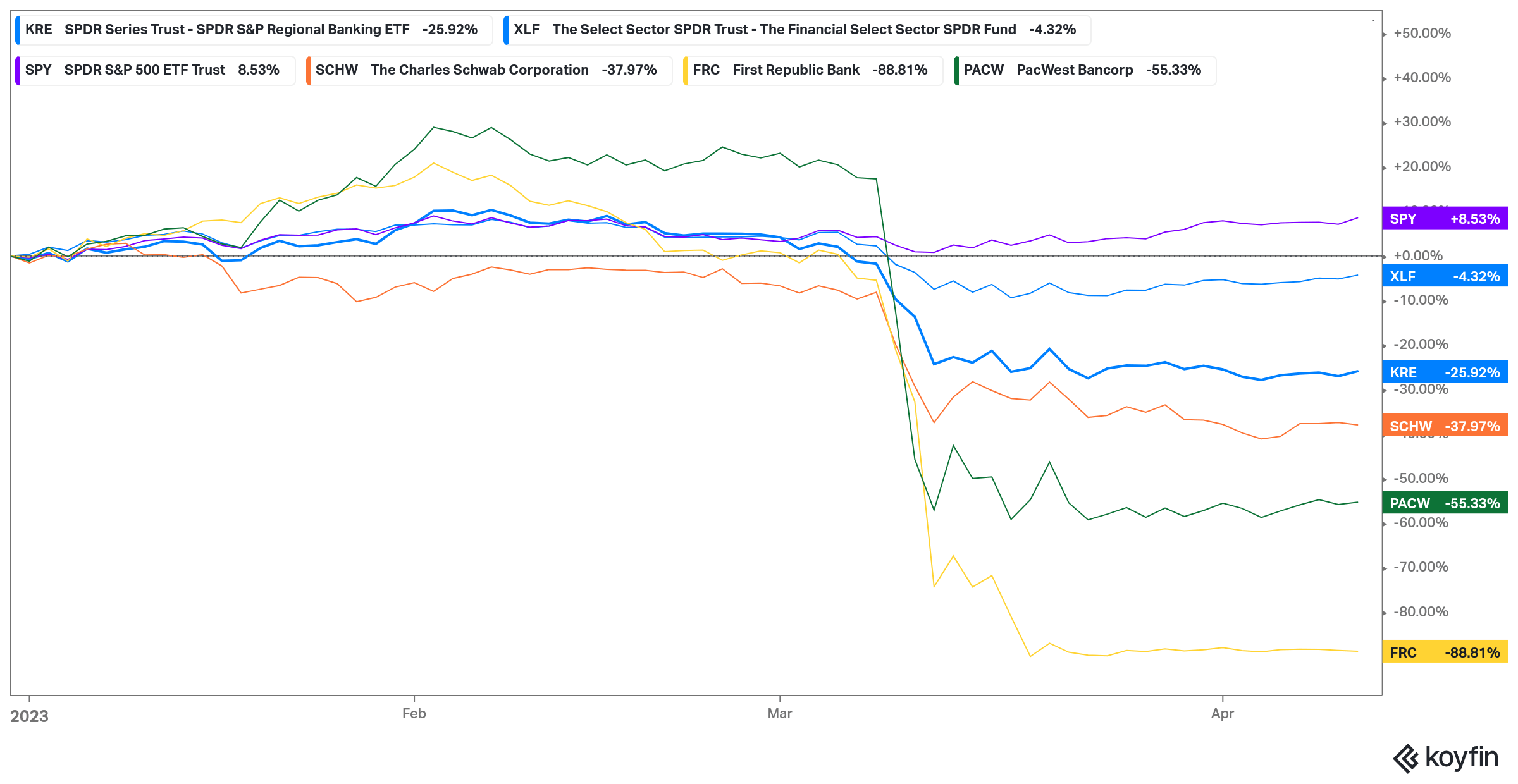

But fast forward to March 2023, and we’ve had 3 bank failures so far: Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Signature Bank, and Silvergate Bank. With $209 billion in assets, SVB was the 16th largest bank in the US and the largest bank failure since 2008. These failures have sparked fears of bank runs on smaller banks. First Republic Bank has lost over $70 billion in deposits, and concerns are swirling over the unrealized losses on held-to-maturity bonds of mid-sized banks like Schwab, which is leading to a deposit flight.

On the other side of the pond, Swiss authorities forced a shotgun wedding of perennial basket case Credit Suisse with UBS. The question on people’s minds now is: will Deutsche Bank, another evergreen European basket case, finally implode?

As Morgan Housel says, risk is what you don’t see.

Such has been the change in sentiment that people went from worrying about the evaporating value of their diversified portfolio of shitcoins to whispering in raspy asthmatic voices, “Oh crap, it’s 2008 all over again.” Probably not, but famous last words and all.

This crisis, if it can be called that, has once again raised the same old questions that we all ask during every crisis. From obvious questions like “Are the banks okay?” to messy questions like “What is money?” and “Why do we put up with banks if they keep messing up?” to profound questions like “Do we need banks?”

Everything that can be written about why Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and Silvergate failed has been written already; I don’t have anything new or useful to say. I’ll include links to some brilliant analyses and opinions. What interested me about this episode were the lesser-appreciated factors like the role of narratives and the long-run implications of banking crises.

Some loosely formed thoughts.

Sensemaking

Most people don’t appreciate just how important narratives are, not just in markets but in real life as well. The SVB crisis once again highlighted the importance. We are storytelling creatures. Ever since our ancestors started rubbing rocks together and figured they could draw with them, they’ve been telling stories.

Stories were pivotal in our evolution. They helped us to learn, find meaning, communicate, cooperate, build relationships, reproduce, and overcome adversity. Humans also hate uncertainty so much that it hurts—nothing is more painful than not knowing something.

To deal with uncertainty, our brains constantly look for patterns and explanations to make sense of things. Our brains arrange things in a coherent manner and discard information that doesn’t fit to make sense of the world. That’s why we often turn to God when we struggle to make sense of something. Recent studies have shown us that reality is not necessarily an objective truth, but rather something that our brains construct or even make up. In a way, our identity is shaped by the stories we tell. We are, in a sense, the stories we tell.

What was fascinating about the Silicon Valley Bank Crisis was that you had a real-time preview of how the creation and propagation of stories affected the markets, depositors, and policymakers’ actions. A crude caricature of modern finance and economics is that it assumes that people are rational agents that consider all available information and make optimal choices in their self-interest. A crude caricature of criticism of economics is that it’s become too mathy, over-reliant on simplistic models, and ignorant about how humans behave.

We can debate this until Royal Challengers Bangalore (RCB) win the Indian Premier League (IPL), but neither will RCB win nor will this debate end. But the criticism that modern finance and economics are ignorant about the nuances of human behavior and its impact on markets and economies is right. The arguments of the behavioralists confirm my priors.

Our models of markets and economics don’t account for the complexity of human behavior, and no, I’m not gonna use the terms “biases” and “rationality.” We are not pathetic creatures incapable of picking a low-fat vegan, gluten-free sandwich. The notions of bias and rationality are complicated, and you have to think about them through an evolutionary lens [1, 2, 3, 4, 5].

But I’m digressing.

Economists have been analyzing the impact of stories on markets for a long time [1, 2, 3, 4]. However, the topic received long overdue and much-deserved attention when Nobel laureate and one of the founding fathers of behavioral economics, Robert Shiller, published “Narrative Economics,” summarizing his decades of work. Professor Shiller likens stories or narratives to viruses (going viral) and says similar to viruses, stories are contagious and mutate as they spread, affecting markets and economies in unpredictable ways.

The form of the narrative varies through time and across tellings, but maintains a core contagious element, in the forms that are successful in spreading. Why an element is contagious, when it may even “go viral,” may be hard to understand, unless we reflect carefully on the reason people like to spread the narrative. Mutations in narratives spring up randomly, just as in organisms in evolutionary biology, and when they are contagious, the mutated narratives generate seemingly unpredictable changes in the economy.

Robert Shiller

The idea that information can spread like a virus is not new. Social scientists, biologists, writers, and others have been using this framing since at least the 19th century. It’s even central to the plot of Neal Stephenson’s “Snow Crash,” published in 1992, and the movie “Inception.” Neil Gaiman also touched on this idea in his awesome 2017 talk.

Looking at how stories spread is a useful way to understand not just the Silicon Valley Bank crisis, but markets in general. However, I’ll focus on the SVB crisis for now. It was a perfect opportunity to see in real-time how stories were spreading and causing ripple effects on markets and the economy.

Multiple people were spreading numerous narratives, each with their own unique motivations.

- Some people wanted o make sense of things.

- Humans are signaling animals. Consciously or unconsciously, people do things to signal that they’re rich, beautiful, strong, etc. Some created narratives because they wanted to signal to the world (and Tinder) that they were “banking experts.”

- Crises are an excellent opportunity to become famous. Some people were spreading narratives with the explicit or implicit goal of becoming popular.

- And the strongest reason of all—self-interest. There was a small group of VCs and founders who were spreading narratives of doom and gloom because they had their money stuck in SVB.

- And then some just wanted to watch the world burn.

As the doom and gloom narratives spread, smaller regional banks sold off. Depositors started fleeing smaller banks and rushed into larger banks and money market funds. It may or may not have sped up the long pending demise of Credit Suisse.

With the click of an iPhone, $US42 billion left one bank in one day. To give you a sense of the order of magnitude, in the financial crisis of ’08, one bank lost $US17 billion in a week,” he said. “So the rate of withdrawal was twenty times what it was then.

James Gorman, CEO of Morgan Stanley

You can trace all popular narratives to what Jean Tirole and Armin Falk call “narrative entrepreneurs.” These people want to get people to behave in a certain way or take advantage of a situation—like Bill Ackman shorting something and crying on Twitter. These narratives spread through both strong and weak ties we have with others.

Rajkamal Iyer and Manju Puri used epidemiological models similar to Robert Shiller in Narrative Economics to analyze a bank run and how the contagion spreads. They analyzed a run on a cooperative bank in Gujarat in 2001, which led to a run on a different bank that had no connection to the bank facing the run. They found that social networks played an important role in causing runs:

We further want to understand how contagion effects of bank run behavior spreads among depositors. For this purpose we explore and employ methods from the rich epidemiology literature that spends considerable effort in examining how diseases spread. We further want to understand how contagion effects of bank run behavior spreads among depositors. For this purpose we explore and employ methods from the rich epidemiology literature that spends considerable effort in examining how diseases spread. Using these models we are able to estimate and quantify transmission probabilities. We estimate the average transmission probability is 3% via social groups (introducer network) and 5% via neighborhood (neighborhood based network). We also find that contagion due to social networks peaks in the second day of the crisis. We discuss implications in terms of timing of regulatory or preventive measures.

Understanding Bank Runs: The Importance of Depositor-Bank Relationships and Networks

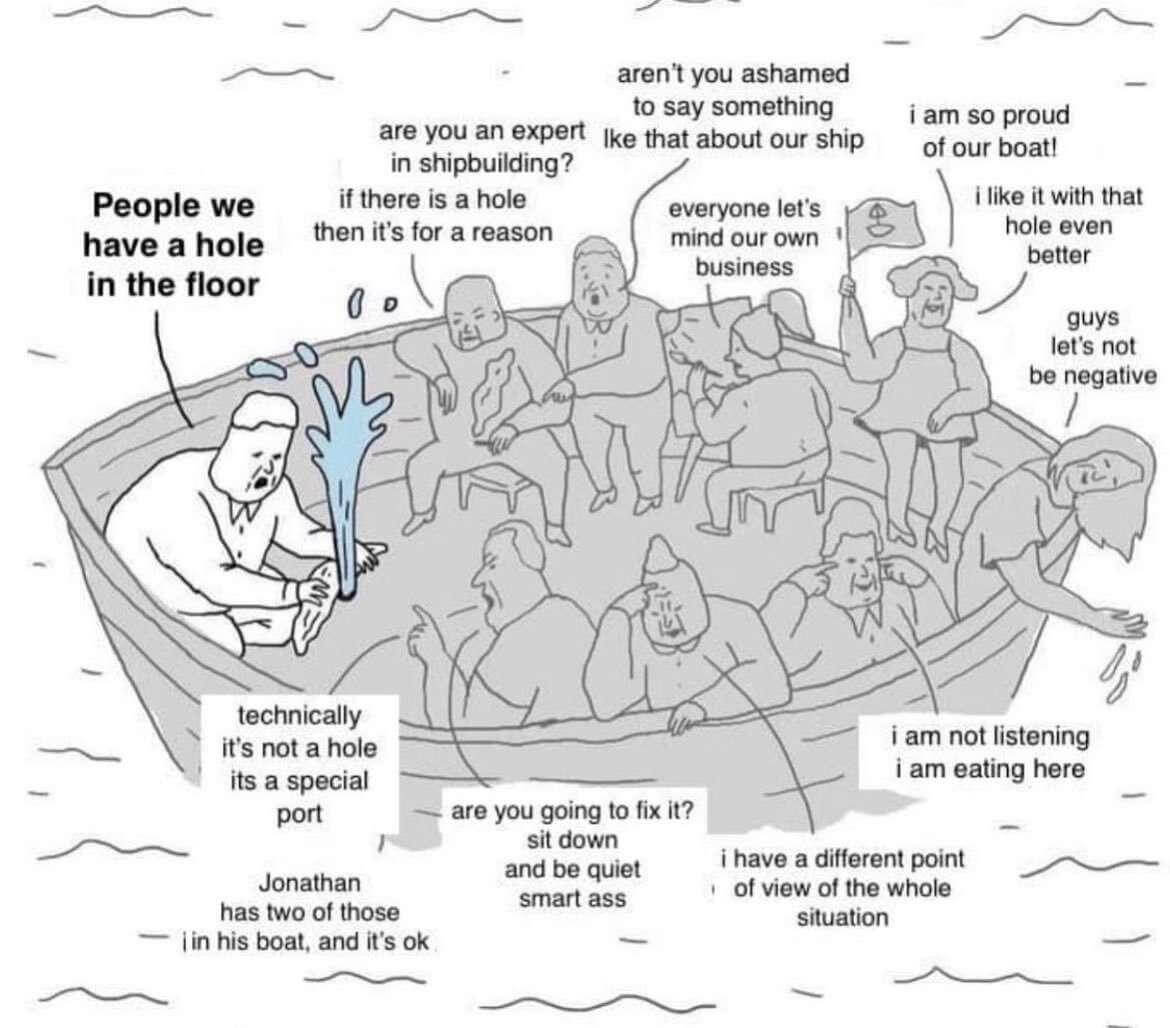

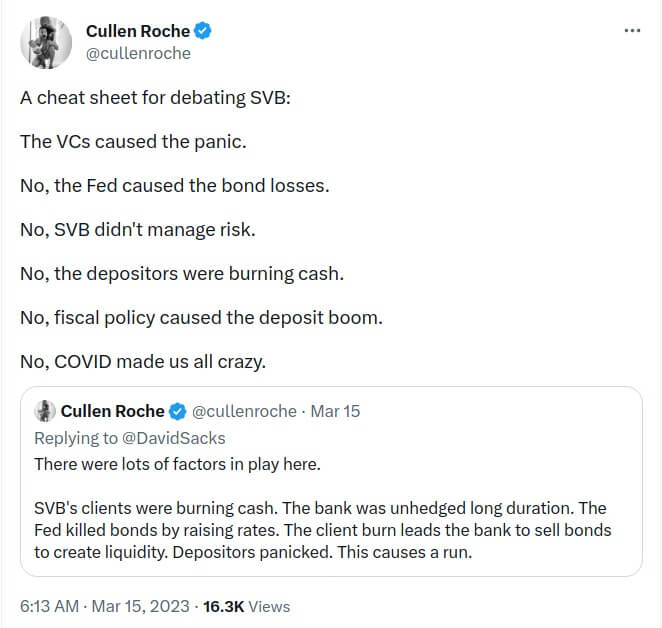

As the crisis unfolded, you could see that the simplest narratives were spreading the most. Narratives like SVB failed because of an asset-liability mismatch, poor risk management, large unrealized losses on their HTM book, social media causing the bank run, etc. But this was the case with many other banks as well. They were necessary but not sufficient conditions.

SVB’s failure was a result of a confluence of factors that were a long time in the making. It started with the impact of COVID, which led to a boom in venture capital (VC) investments and a surge in deposits at SVB. This, in turn, attracted libertarian startup tech enthusiasts who were interconnected with each other. However, the subsequent rise in inflation caused the Fed to hike rates, resulting in losses on SVB’s HTM bond book, which had a significant duration. These mark-to-market (MTM) losses were exacerbated by regulatory changes implemented after the 2008 financial crisis. As SVB scrambled to raise money to address the situation, falling stock prices further impeded their efforts. Panic ensued among the tech enthusiasts, leading to coordinated efforts in chatrooms to withdraw money from SVB, fueled by social media and mainstream media coverage. The resulting panic led to more requests to pull out money, forcing SVB to pledge assets to meet withdrawals, only to be thwarted by the outdated payments system of the Fed created in the 8th century. Ultimately, these circumstances rendered the bank insolvent, leading to the FDIC taking the bank into receivership.

But, by the time you finish this answer, you will either have been the victim of physical violence, or your friend will have driven to the nearest supermarket, bought a carton of eggs, dumped it on your head, and sprinkled some glitter for good measure.

Complex events can’t be explained with simple answers, the real answers always involve a lot of ifs and buts, but such answers are uncool. We always look for simple explanations for complex events because being right feels good damn it—it’s just like being high on cocaine. This is the same reason fake news spreads faster than real news—because our brains weren’t built for thinking.

I listened to Kate Judge, law professor at Columbia Law School, and Peter Conti-Brown, associate professor of financial regulation at Wharton, talk about the SVB crisis on Macro Musings. I was struck by how many times Professor Judge kept saying that we didn’t know everything yet.

I mean, clearly there’s a lot of different factors going on. So you’re never going to be able to have a simple narrative of, here’s the one party that was at fault, or here’s the one story of what went on. There were a series of missteps. And there shouldn’t be a series of missteps, not only that leads to a bank failure, but leads to actually three bank failures

Kate Judge

I hate to be a broken record on this, but again, I think we have yet to fully know.

Barry Ritholtz had written a post along the same lines. It’s remarkable how much we despise saying, “I don’t know.”

In our drive to make sense of things, we force order and meaning to events where none exists. You can see this tendency to make sense of things in the markets every day. This reminds me of a wonderful article on Zerodha Varsity:

What moves the market? It’s traders and investors making informed and uninformed decisions. They use sophisticated technical systems, complex fundamental approaches, tips, hunches, guesses, bad information and even astrological signs to make their decisions to buy, sell, or stand aside. All the educated and uneducated conjectures are tossed in the pits and the market is pushed or pulled to a higher or lower close. It, meaning the market, has nothing to say about the daily results. It, meaning the market, has nothing to say about the daily results. That’s why you must not anthropomorphize it. Take it for what it is—a dumb, inanimate blob.

“Chaos was the law of nature; Order was the dream of man.” ― Henry Adams

Trust and faith

I felt smart when I came up with the phrase, “Banking is a confidence game.” But my smartness bubble was violently deflated as I learned that other people had said this before me. Sed 🙁

Banking is indeed a confidence trick because, as Tobias Carslile put it, banks are technically insolvent all the time since they can’t meet all the withdrawals at the same time. Trust is the glue that holds modern capitalist economies together. Loss of trust can wreak havoc. Given how interconnected the modern financial system is, a loss of trust can spread faster than a silent fart in a crowded room with closed windows.

Loss of trust in banks can have devastating consequences since our everyday lives and economic activities rely on the implicit trust that banks will safeguard our money. Loss of faith in banks is not only deadly, but the distrust lingers for a long time. I don’t want to litigate whether bailing out SVB and Signature Bank was the right move. The depressing thing about the debates over the bailout was the lack of nuance about the fallout from bank failures.

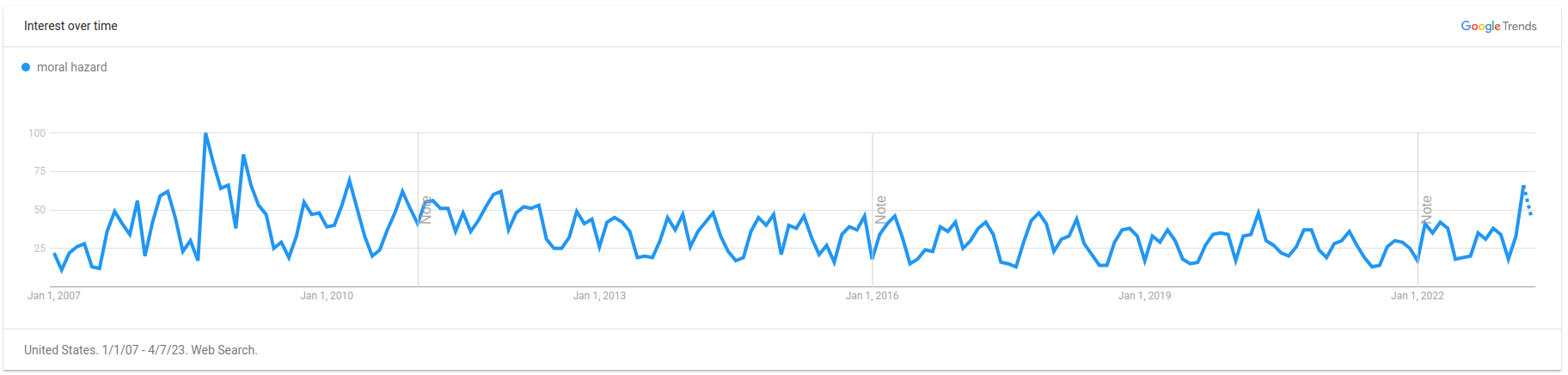

The even more depressing thing was that the term “moral hazard” was once again in vogue. People who drank bleach to cure COVID suddenly transformed into experts on moral hazard. These people were and are insufferable 🙁

Critics have been shouting that guaranteeing all the deposits of Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank will cause banks to be reckless because they’ll assume that all deposits are guaranteed. What made this bailout toxic was that some of the depositors in the case of SVB were rich venture capitalists like Peter Thiel.

Forget the 2023 season of bank bailouts; we’re still arguing 15 years later about whether bailing out the big banks in 2008 was the right decision. This crisis has once again highlighted the centrality of banks, not just as custodians of people’s money but as central nodes through which all the money in a system flows. This reminds me of Matt Taibbi’s evocative description of Goldman Sachs in 2010:

The first thing you need to know about Goldman Sachs is that it’s everywhere. The world’s most powerful investment bank is a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.

If you are a cynic, then this is a perfect description of banks, but I digress.

Bailing out banks is never an easy decision, especially when the rich are presumed as the primary beneficiaries, as in the case of SVB. There’s nuance to this presumption. Some startups often banked with SVB because the other banks wouldn’t touch them, while others chose SVB because of the sweetheart deals they got from SVB. But you can’t have tailor-made bailouts where you check every depositor’s net worth to see if they’re rich or poor; it can only be a blanket guarantee.

Everybody is debating whether bailing out banks was right or wrong, so there’s no point in beating a dead horse. Beating dead horses is not good. What was missing in this debate was the impact of bank failures on society. Even a cursory look at the history of bank failures shows that banking failures can have a devastating impact. Of course, the SVB crisis isn’t systemic, but it’s not hard to imagine an alternate reality where the regulators didn’t act and the contagion spread to other banks.

As many of the theoretical models and some evidence suggest, even if the bank is fundamentally solvent, bank runs can still occur because depositors can run in anticipation of a run.

Understanding Bank Runs

Finally, early and widespread interventions are an important tool to arrest panics, limit the contraction of the banking sector, and ameliorate their impact on the economy. Historical crises that have not benefited from intervention have been particularly costly.

Ok, how bad can bank failures really be?

In a 2019 study, Sebastian Doerr and co-authors found that the German banking crisis starting in 1931 played a crucial role in the popularity of Hitler:

Greater economic collapse was one important mechanism that links the banking crisis to Nazi voting. While unemployment did not affect Nazi votes, income declines driven by exposure to Danatbank and Dresdner Bank (DD) strongly increased support for the Nazi party (NSDAP) – a one standard deviation decline in income caused by DD was associated with a 4.3% rise in Nazi support (while the average change in NSDAP vote share from 1930 to 1933 was 22%). In contrast, a one standard deviation change in income (not predicted by DD exposure) increased Nazi votes by only 1.1%.

Financial crises and political radicalization: How failing banks paved Hitler’s path to power.

Hitler!

In his magisterial book “Crashed,” historian Adam Tooze paints a sordid picture of how myopic, self-defeating, and exclusionary decisions by policymakers supercharged political polarization and led to the rise of right-wing parties on both sides of the Atlantic. What’s ironic is that Donald Trump, who took advantage of the simmering resentment among Americans about the 2008 crisis to come to power, had a role to play in the demise of SVB by weakening banking regulations in 2018.

This is corroborated by other evidence as well:

When the imposition of the 1933 U.S. Silver Purchase program drained Chinese banks of silver, firms reliant on those banks that were more exposed to silver outflow experienced more labor unrest and Communist Party membership growth among their workforce Braggion et al. (2020).

When the imposition of the 1933 U.S. Silver Purchase program drained Chinese banks of silver, firms reliant on those banks that were more exposed to silver outflow experienced more labor unrest and Communist Party membership growth among their workforce Braggion et al. (2020).

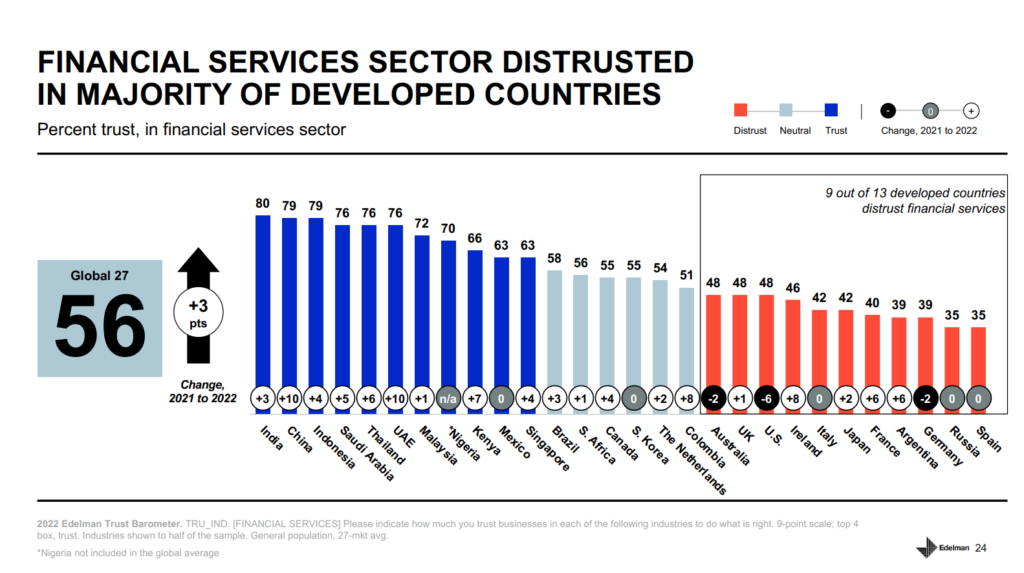

It’s no wonder that numerous surveys indicate that trust in banks never fully recovered after the 2008 financial crisis. Distrust in banks and monetary authorities can leave deep scars that persist for generations. The failure of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, which was established to serve black Americans in 1876, continues to have repercussions to this day. Peer-to-peer (P2P) lending and crowdfunding gained popularity in the US after 2008, partly due to the mistrust of banks. Hyperinflation and currency controls in Argentina have resulted in a thriving black market for dollars, making life tough for policymakers. In Lebanon, people rob banks not to steal money but to withdraw their own money.

“All the world is made of faith, and trust, and pixie dust.” ― Friedrich Nietzsche

Invisible scars

Let’s go back to the crude caricature of neoclassical economics I painted earlier. The fundamental assumption in standard economic models is that people are rational utility maximizers. They consider all available information, constantly update their knowledge based on new evidence, have perfect memory, and make optimal choices by weighing all probabilities. Around the 1950s, people started to push back against this ridiculous notion, and so began the behavioral revolution, which made economics much less dismal.

Thanks to the behavioral revolution, a new generation of economists has given rich insights into the complexities of human decision-making. One of the rising stars in the field of behavioral economics is Ulrike Malmendier, a professor of finance and economics at Berkeley. Professor Malmedndier has done some amazing research on experience-based learning or experience effects. Her work complements existing economic research on similar topics.

All these approaches look at how past experiences shape future decision-making. Only economics can be so dumb as to ignore something that sociologists and psychologists figured out decades ago. This is similar to how economists have long neglected the role of narratives in shaping economics that Professor Shiller talks about in narrative economics. The oldest reference I know of to the idea that our past affects our lifelong behavior is in Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory from the 19th century.

Across multiple studies in different settings, Professor Malmendier has shown that our lived experiences affect our decision-making, risk preferences, consumption choices, and beliefs throughout our lives. Our past experiences affect everything from how we invest, the type of jobs we choose, inflation expectations, mortgage choices, how much we spend on food, etc.

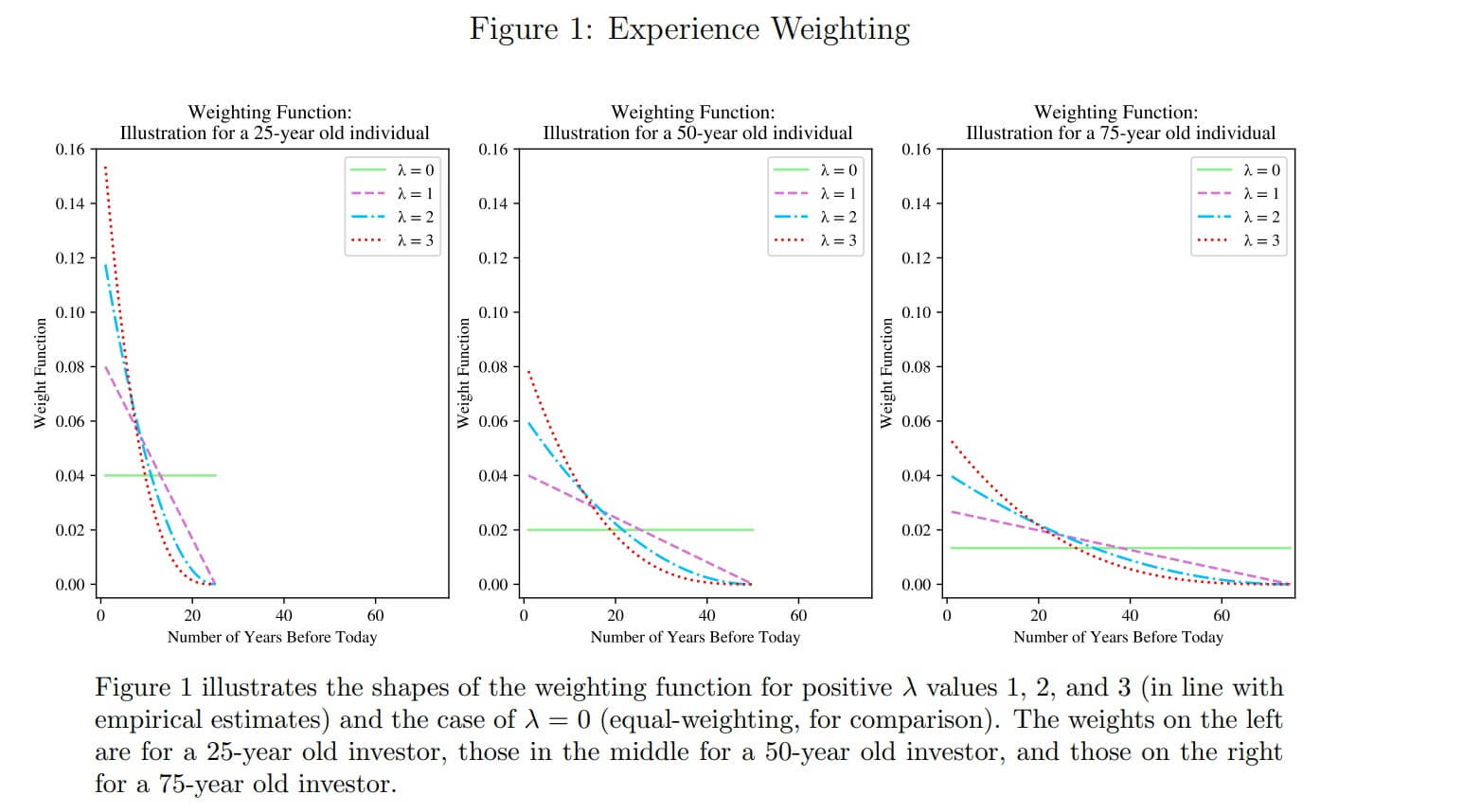

In what I consider a seminal paper, she showed how the great depression of the 1930s shaped the risk preferences of the generation that lived through it. Depression babies who lived through the 1930s had low stock market participation compared to later generations. People who experience a market crash early in their lives take lesser financial risks when controlling for major variables. The striking thing is that these aren’t short-run effects; even though the effects decay over time, they still persist over the lifetime. In other words, we overweight our most recent experiences. Younger generations overweight their most recent experiences compared to older generations.

This is corroborated by other research as well. Christopher Severen and Arthur van Benthem found that kids who experience high oil prices during the ages of 15–18, when they typically learn to drive, tend to drive less throughout their lives.

Experience-based effects don’t just show up in the stock market, but across multiple domains.

- People who have experienced high inflation in their lifetimes are more likely to buy houses with fixed-rate mortgages because they overestimate future interest rates.

- Smart people aren’t immune to experience-based effects. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) members who have experienced higher inflation in their lifetimes tend to be more hawkish and vice versa.

- People who experience higher grocery prices tend to have higher inflation expectations when compared to other households or market expectations.

- People who have been unemployed in the past tend to be pessimistic about their future financial situation and spend less despite the lack of correlation between past experiences and future incomes.

- People who have lived under communist rule are less likely to participate in the stock markets. To the extent they participate, they tend to invest in stocks of other communist counties and are less likely to invest in American companies, especially financials.

I would love to see more studies specifically looking at the impact of the experience-based effects of banking failures and crises. But the existing studies and available data show that people who experience banking crises trust banks less. Time series data from surveys is hard to come by, but you can draw reasonable conclusions based on the available data that the countries that had the worst banking crises during the 2008 and Eurozone crises have the lowest trust in banks and financial services companies.

As I was writing this post, I came across this wonderful paper bu Carola Frydman and Chenzi Xu. Here’s an excerpt:

Banking crises have large negative effects on the real economy. Shocks to financial institutions affect a wide range of outcomes, from employment and output to political participation. Although the magnitudes of the effects of disruptions to credit intermediation on real outcomes are hard to contrast across studies, they are often large and long-lasting.

Living through a banking crisis may also affect long-term outcomes by shaping the risk preferences of a generation. Individuals that experienced low stock market returns throughout their lives report in survey data to be less willing to take financial risk and to participate in the stock market (Malmendier and Nagel, 2011). Koudijs and Voth (2016) lever a historical event to validate this view. In 1772, an investor syndicate speculating in Amsterdam went bankrupt. While distress was publicly known, lenders who were exposed but did not lose any money altered their behavior relative to unexposed ones, asking for much higher haircuts after this experience.

Banking Crises in Historical Perspective

My favorite anecdotal story about trusting banks is from financial psychologist Brad Klontz. Talking about his mom and dad on the Hidden Brain podcast, he says the following:

She grew up in Detroit and went to high school. And she went to a high school where there was half the school was poor and the other half had money. And so she was one of the poor ones and she felt extremely self-conscious about this, anxious about it. And as she’s talking about it, I’m seeing, oh, okay, so I get why I’m anxious. This is starting to make sense. And then I asked her, “What was it like for grandma and grandpa growing up around money?” And this blew me away.

So first of all, I knew we didn’t have money. And so at this point, my grandparents, they’re living in a trailer park community. So I know we didn’t have much money, but I know everyone’s really hardworking and smart. So this was one of the mysteries I had in my mind. And I found out that my grandfather went to the bank as a young man, right during the Great Depression and all the money was gone. And then my mom said that your grandfather never put a dollar in the bank again the rest of his life. Now, he lived into his nineties. He kept all of his money in a lockbox, either in the attic or under his bed.

They absolutely do. And that’s what I found to be true in my own experience. I realized that my grandfather’s trauma… I mean, what does that experience tell you? What do you walk away with in terms of understanding money in the world? And it’s like, well, very clearly you can’t trust banks with your money. Then my mother’s reticence to invest anything. She wouldn’t invest in anything. She bought CDs in the bank, but she would not put money in the stock market. And all of a sudden that makes sense to me. And so then this is the real light bulb moment for me is I did what I call a dysfunctional pendulum swing, right? You see this quite often in extreme behaviors. For example, if you grew up with an alcoholic parent, some people either become alcoholics themselves or they never touch the stuff.

Past crises don’t only shape individuals but also institutions—after all, institutions are collections of individuals. Another study from Professor Malmendier shows that past banking shocks affect the future risk-taking of banks. This reminds me of former Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernake’s actions in 2008. Before joining the Fed, a large body of his scholarly work was devoted to studying the great depression. You could argue that his dramatic actions during 2008 were driven not only by an incentive not to be seen as a chairman who oversaw another depression but also by his study of the depression, which would’ve left a lasting imprint. In the same vein, you could argue that the equally dramatic actions of the Fed under Jay Powell to backstop the entire financial system in 2020 were the result of the institutional memory of fighting the 2008 crisis.

Further reading and listening

Nathan Tankus has emerged as one of the more interesting and thoughtful thinkers about all things monetary economics. On his blog, Notes on the crises, he has published some incisive pieces on not just the SVB collapse but deposit insurance, shadow banking, and the Federal Reserve’s actions. I highly recommend reading all the pieces.

Rohan Grey is one of the most thoughtful thinkers about money and banking from an MMT lens. His Twitter feed has some brilliant observations, not just about the crisis but about the construct of money itself. I came across this podcast which I haven’t heard yet but added to my playlist

Elham Saeidinezhad is a term assistant professor of economics at Barnard College, Columbia University. She wrote a brilliant four-part series on the SVB crisis on her blog, and it’s a must-read. She also wrote a shorter piece on Phenomenal World. One of my new rabbit holes is diving through Professor Saeidinezhad’s work.

Christine Desan, Lev Menand, Raúl Carrillo, Rohan Grey, Dan Rohde, and Hilary J. Allen are some of the smartest thinkers on money and banking. The LPE Project curated their incisive takes on the SVB collapse.

Steven Kelly is a senior research associate at the Yale Program on Financial Stability. He’s written some interesting posts about SVB and Credit Suisse. His Twitter feed is full of interesting observations about the crisis as it continues to unfold. I also enjoyed his chat with David Beckworth on the Macro Musings podcast.

Morgan Ricks is a professor of law at Vanderbilt University, a former Treasury official, and the author of The Money Problem: Rethinking Financial Regulation. This is one book I can’t wait to read because Professor Ricks is damn thoughtful. He’s been tweeting and writing about the crisis and, more importantly, about why getting rid of deposit insurance limits is a good idea.

In a similar vein, historian Peter Conti-Brown has also been tweeting and writing some thought-provoking things about the banking crisis, banking regulation, and deposit insurance that are in disagreement with Morgan Ricks. His joint appearance on the Macro Musings podcasts was really good.

In the wake of the SVB collapse, a lot of people drew parallels to the Savings and Loan (S&L) crisis of the 1980s. Anna Gelpern, a legal scholar and professor of law and international finance at Georgetown University Law Center, wrote a brilliant piece on how this crisis is different from the S&L crisis.

This paper by Carola Frydman and Chenzi Xu summarizing the literature on historical banking crisis is amazing and a must-read.

Jiang et al. (2023) calculate the mark-to-market losses on held-to-maturity bond portfolios of banks and look at factors that lead to runs.

The SVB crisis once ignited the debate over the need for a narrow bank that takes deposits and holds them at the Fed or invests only in treasuries. The Federal Reserve had in 2018 rejected an application for a narrow bank. Brian Romanchuk published an interesting post on why there’s no need for a narrow bank.

Saule Omorova is one of the foremost scholars on financial regulation and a professor of law at Cornell Law School. She was also nominated to head the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) by Joe Biden, but her nomination was derailed due to a vicious smear campaign by the banking lobby that branded her a communist. One reason why her nomination was derailed was that she was a big proponent of reining in banks. In a paper titled The People’s Ledger, she took the idea of a CBDC to its logical conclusion and proposed that people should be allowed to directly open accounts with the Federal Reserve. In her vision, banks would be reduced to acting as agents of the Fed. Her other equally amazing paper that has shaped my own thinking about money is The Finance Franchise. These are just two topical papers related to the SVB collapse, but her entire body of work, especially on fintech, is fascinating. I highly recommend checking everything out. She was recently on the Odd Lots podcast as well.

Steve Roth wrote a post with a very similar proposal.

Lev Menand is an associate professor of law at Columbia and one of the foremost experts on central banking, having worked at the treasury. He also recently published another book I can’t wait to read, The Fed Unbound: Central Banking in a Time of Crisis. He was on the Odd Lots. I highly recommend checking out all his papers, videos, and podcasts.

Of course, this list isn’t complete without a mention of historian Adam Tooze. Judging by the amount of stuff he publishes, I have my doubts about whether he is human. Anyway, he’s published several amazing posts not just on SVB but on banking and regulation as well.

Similarly, the list cannot be complete without the awesome Matt Levine. All his posts, not just about SVB, but ALL his posts are ALWAYS mandatory reading.

Frances Coppola is one of the most thoughtful writers on modern banking. All her posts are mandatory reading as well.

I always learn new things from Cullen Roche and he has a gift for simplifying complex topics. His posts on the crisis are really good.

Why markets can never be made truly safe.

The IMF Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR)

Jacobin seems have a nice series of perspectives that I haven’t yet read.

Huw van Steenis suggests how digital bank runs can be prevented.

Why Do We Even Need Private Banks?

What Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse tell us about financial regulations

The American Prospect has a good series on what’s next after SVB.

Jamie Cathewood looks at historical banking runs and panics.

The Great Depression, banking crises, and Keynes’ paradox of thrift

Bank networks and systemic risk in the Great Depression

Bill Dudley on Lessons From the Banking Crisis

Raghuram Rajan: Why The Banking Crisis Isn’t Over

That Substack thingy.

Leave a Reply